sabachthani

Ἐλωΐ Ἐλωΐ λαμὰ σαβαχθανί

Jesus uttered roughly what sounded like this, as he was “exhaling his life.”

(In the text, they're phonemes, not words, not grammar)

Table of Contents:

- Sources

- The case for phonetic words

- Lost in translation, why translators assumed Aramaic

- The question marks were added later

- Hipta verse - shows how Greeks call chthonic powers

- The cry

- Saba (σαβα)

- Sabaoth (σαβαωθ) - previous use is seen in the PGM as a ritual incantation

- Chthonie (χθονίη)

- Saba (σαβα) Cthonie (χθονίη)

- saba chthanie (σαβα χθανίη)

- Heli Heli, Eloui Eloui, Euoi Euoi

- euoi euoi - the bacchic cry of life

- sabai - saba revisited, another Bacchanalian cry, like euoi

- lama/λαμὰ or lema/λεμὰ

- Codex Vaticanus gives dzabaphoane (or phthane)

- Final, dead simple version

- In Orphic Cosmology

- Alternate translations

Sources

We have 2 sources of this utterance:

- Mark 15:34 (Greek New Testament, Nestle 1904)

- Matthew 27:46 (Greek New Testament, Nestle 1904)

καὶ τῇ ὥρᾳ τῇ ἐνάτῃ

And at the ninth hour

ἐβόησεν ὁ Ἰησοῦς φωνῇ μεγάλῃ·

Jesus cried out with a loud voice

Ἐλωΐ Ἐλωΐ λαμὰ σαβαχθανί·

(phonetic cry preserved as sound)

ὅ ἐστιν μεθερμηνευόμενον·

which is being interpreted / translated

ὁ θεός μου ὁ θεός μου,

my god, my god

εἰς τί ἐγκατέλιπές με;

for what / toward what have you abandoned me

- ἐβόησεν is from βοάω — “to cry aloud, shout, cry out” (LSJ)

This is not calm speech.

It is a loud vocal emission — exactly how ritual cries are described.

περὶ δὲ τὴν ἐνάτην ὥραν ἀνεβόησεν ὁ Ἰησοῦς φωνῇ μεγάλῃ λέγων·sometimes as:

Ἡλί Ἡλί λεμὰ σαβαχθανί

Ἡλεὶ Ἡλεὶ λεμὰ σαβαχθανεί

Same structure:

- loud cry

- doubled name

- phonetic variation (Ἐλωΐ / Ἡλί)

- same final sound-cluster

Matthew clearly copies the sound, not the grammar.

That’s why the spelling shifts.

The case for phonetic words

The words traditionally rendered as heli heli lama sabachthani are best understood as phonetic vocalizations (phonemata/φωνήματα) rather than grammatical language. This conclusion follows directly from the instability of spelling across the earliest Greek witnesses, especially when those witnesses preserve scriptio continua (continuous writing without spaces).

Crucially, the oldest versions contains no spaces or punctuations.

When we remove that assumption, the textual evidence points instead to preserved sound, not preserved syntax.

Ἐλωΐ Ἐλωΐ λαμὰ σαβαχθανί

eloui eloui lama sabachthani

Ἡλί Ἡλί λεμὰ σαβαχθανί

heli heli lema sabachthani

sometimes as:

Ἡλεὶ Ἡλεὶ λεμὰ σαβαχθανεί

helei helei lema sabachthanei

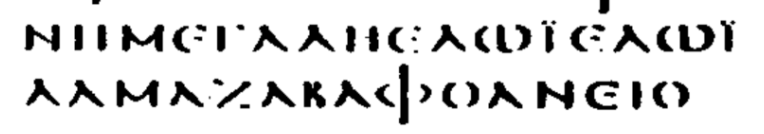

ελωιελωιλαμαζαβαφοανε

elouielouilamadzabaphoane (or phthane)

with spacing:

ελωι ελωι λαμα ζαβαφοανε

eloui eloui lama dzabaphoane (or phthane)

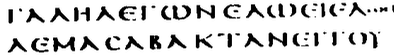

ΕΛΩΕΙΕΛ(ΩΕΙ)ΛΕΜΑϹΑΒΑΚΤΑΝΕ

ELOUEIELOUEILEMASABAKTANE

with spacing:

ΕΛΩΕΙ ΕΛ(ΩΕΙ) ΛΕΜΑ ϹΑΒΑΚΤΑΝΕ

elouei elouei lema sabaktane

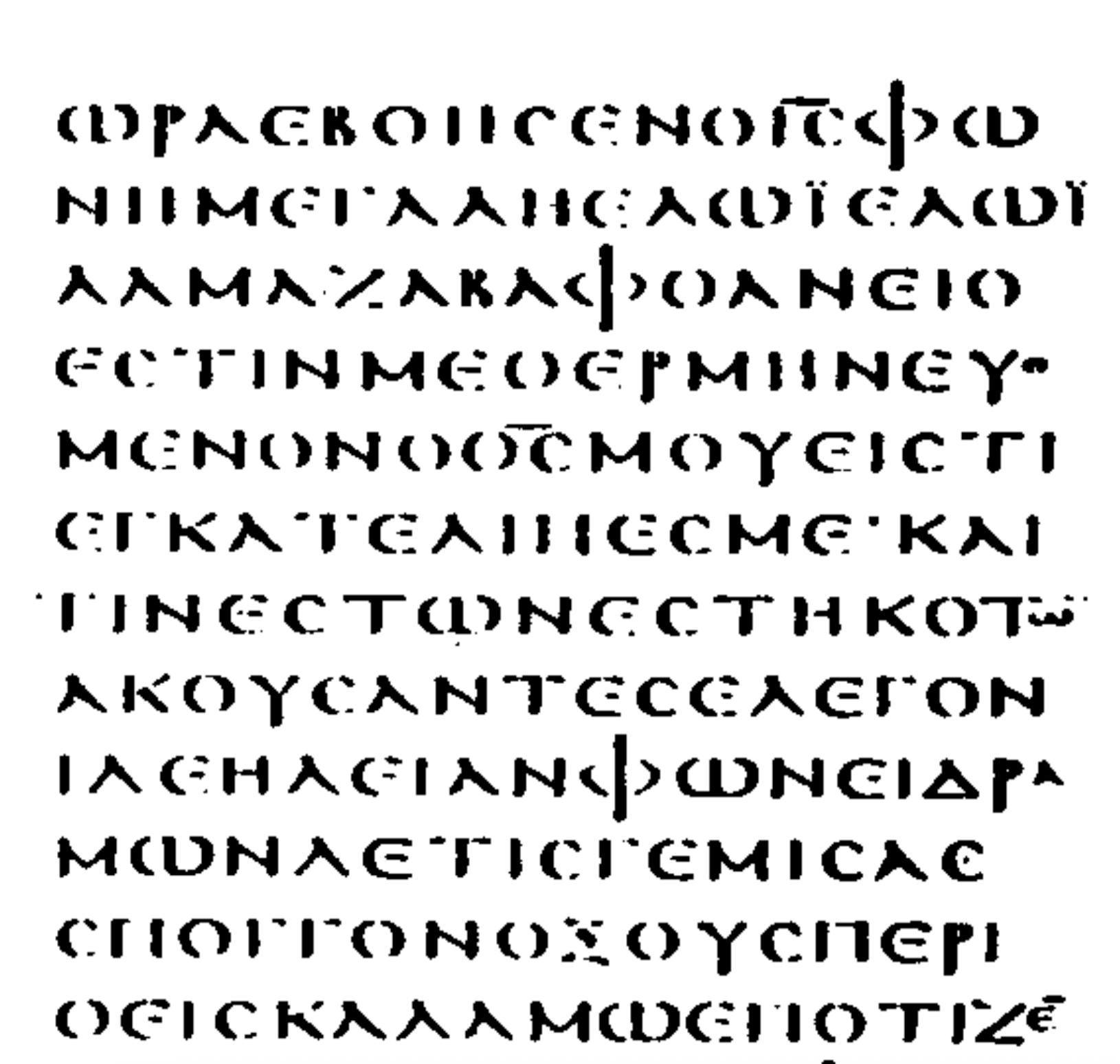

ΕΛΩΙΕΛΩΙΛΑΜΑΣΑΒΑΧΘΑΝΙ

ELOUIELOUILAMASABACHTHANI

with later editorial addition of spacing + punctuation (marks):

Ελωΐ Ἐλωΐ λαμὰ σαβαχθανί

eloui eloui lama sabachthani

ΗΛΙΗΛΙΛΑΜΑΣΑΒΑΧΘΑΝΙ

elielilamasabachthani

with later editorial addition of spacing + punctuation (marks):

Ἠλί Ἠλί λαμὰ σαβαχθανί

eli eli lama sabachthani

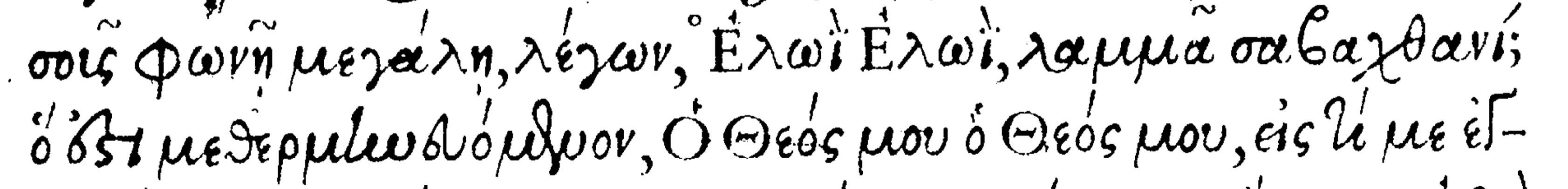

Novum Testamentum Graece, ed. Desiderius Erasmus, later revised by Robert Estienne (Stephanus) and Theodore Beza. Basel / Paris / Geneva, 1516–1604.

ἐλωὶ ἐλωὶ λαμμᾶ σαβαχθανί

eloui eloui lamma sabachthani

NOTE: some editions choose to print it as Ἡλί ("hay-lee" rough breathing) to indicate an h- sound (“Hēli”), while others print Ἠλί ("ay-lee" smooth breathing) (“Ēli”). But those ancient sources don't decide that — they only give ΗΛΙ.

Lost in translation, why translators assumed Aramaic

At first glance, the phoneme stream preserved in the crucifixion cry was unfamiliar to those witnesses at the scene, unfamiliar to the apostle writers, and unfamiliar to later Christian translators.

The utterance did not resolve into words they expected to hear, and - once the context had been lost - it was natural for later readers to assume the sounds must belong to a foreign language, specifically Aramaic. This assumption was reinforced by the presence of an explicit explanatory gloss in the text itself, which invites translation rather than phonetic preservation.

The explanatory gloss

Immediately following the phonetic utterance, the text adds an explanation (“that is, means...”). This single phrase strongly conditioned how later readers interpret what precedes it.

Here's the phrase after the aforementioned sabachthani line, which confuses translators and those studying this passage.

34καὶ τῇ ἐνάτῃ ὥρᾳ ἐβόησεν ὁ Ἰησοῦς φωνῇ μεγάλῃ Ἐλωῒ Ἐλωῒ λαμὰ σαβαχθανεί; ὅ ἐστιν μεθερμηνευόμενον Ὁ Θεός μου ὁ Θεός μου, εἰς τί ἐγκατέλιπές με;

ὅ ἐστιν μεθερμηνευόμενον

which is interpreted as

Ὁ Θεός μου ὁ Θεός μου, εἰς τί ἐγκατέλιπές με;

“the divine one, my divine one, to what end did you abandon me?”

35καί τινες τῶν παρεστηκότων ἀκούσαντες ἔλεγον Ἴδε Ἡλείαν φωνεῖ.

καί τινες τῶν παρεστηκότων ἀκούσαντες ἔλεγον

and some of those who were standing by, having heard, were saying,

Ἴδε Ἡλείαν φωνεῖ.

“Look — he is calling Elijah.”

46περὶ δὲ τὴν ἐνάτην ὥραν ἀνεβόησεν ὁ Ἰησοῦς φωνῇ μεγάλῃ λέγων Ἡλεὶ Ἡλεὶ λεμὰ σαβαχθανεί; τοῦτ’ ἔστιν Θεέ μου θεέ μου, ἵνα τί με ἐγκατέλιπες;

τοῦτ’ ἔστιν

that is

Θεέ μου θεέ μου,

"O divine one of me, O divine one of me,

ἵνα τί με ἐγκατέλιπες;

to what end did you abandon me?"

47 τινὲς δὲ τῶν ἐκεῖ ἑστηκότων ἀκούσαντες ἔλεγον ὅτι Ἡλείαν φωνεῖ οὗτος.

τινὲς δὲ τῶν ἐκεῖ ἑστηκότων ἀκούσαντες ἔλεγον ὅτι

some, but of the there-standing, having heard, were saying that

Ἡλείαν φωνεῖ οὗτος.

this one is calling Elijah.

We need to keep in mind, that each of those standing there heard different sounds, didn't understand, and instead interpreted what they heard.

It may not be a translation of a foreign language at all.

It may be they just didn't have the context to understand.

The question marks were added later

The Greek question mark (;) is a Byzantine development, centuries later (8th–9th century CE). It does not appear in first-millennium gospel manuscripts (1st c. CE). No punctuation, and often no word spacings either.

So when modern printed editions or translations show:

(phonetic cry preserved as sound)

It's a cry here (not a question), and the question mark could denote uncertainty of the sound. σαβαχθανίη perhaps.

Mark himself adds a prose gloss afterward explaining the cry as if it meant “why have you abandoned me.” Later editors then retrojected that explanation back into the line by adding the question mark ";" punctuation:

which is being interpreted / translated

εἰς τί ἐγκατέλιπές με;

for what / toward what have you abandoned me?

- μεθερμηνεύω — “to interpret, to explain”

He basically says:

Jesus cried out a sound that people didn't understand, thought maybe when he said "eloui" or "Eli" or "heli" (we're not sure) that he was saying something about Elijah , which we're going to explain as “my god, my god, for what have you abandoned me?”

The question mark originates from Byzantine grammatical clarification of the translation line (not of the cry). In the scribal sequence, this question appeared first here, before sabachthani had it's ";" appended:

for what / toward what have you abandoned me?

- εἰς τί — “toward what? for what purpose?”

- This is a legitimate interrogative phrase in Greek prose. A question mark makes sense here for the translation line, not for the cry.

Mark’s structure is:

cry → which is interpreted as → a Greek questione.g.

Jesus cried out a sound that people didn't understand, thought maybe when he said "eloui" or "Eli" or "heli" (we're not sure) that he was saying something about Elijah , which we're going to explain as “my god, my god, for what have you abandoned me?”

The cry itself is not a question.

The punctuation belongs only to the later interpretation layer.

The cry itself is unpunctuated sound, and is an invocation.

When you see a question mark, you are not seeing Mark.

You are seeing a later grammatical decision imposed on Mark’s gloss.

Hipta verse - shows how Greeks call chthonic powers

Ἵππας, θυμίαμα, στύρακα.

Ἵππαν κικλήσκω Βάκχου τροφόν, εὐάδα κούρην,

μυστιπόλον τελετῇσιν ἀγαλλομένην Σάβου ἁγνοῦ,

νυκτερίοισι τε χοροῖσιν ἐριβρεμέταο Ἰάκχου.

κλῦθί μευ εὐχομένου, χθονίη μήτηρ, βασίλεια,

εἴτε σύ γ’ ἐν Φρυγίῃ κατέχεις Ἴδης ὄρος ἁγνὸν,

ἢ Τμῶλος τέρπει σε, καλὸν Λυδοῖσι θόασμα·

ἔρχεο πρὸς τελετὰς ἱερῷ γηθοῦσα προσώπῳ.

Hipta—incense, storax. I call upon Hipta, the nurse of Bacchus, the maiden who cries the Eua-cry (ecstatic shout), the one who serves among initiates and rejoices in the rites of purified Saba, moving in the nocturnal dances of loud-roaring Iacchus. Hear me as I perform my rite, O chthonic mother, queen—whether you dwell in Phrygia holding the holy mountain of Ida, or whether Tmolus delights you, that fair wonder among the Lydians—come to the rites, arriving with a sacred and rejoicing presence.

- εὐάδα κούρην — literally, “the maiden of the euā-cry. The cry here is εὐά / εὐοῖ, the well-attested Bacchic ritual shout. LSJ treats εὐά and εὐοῖ as φωνήματα - ritual vocalizations. They are shouted in dance, intoxication, and initiation to induce and mark ecstatic state

- χθονίη μήτηρ - Here Hipta is the cthonic mother.

Hipta matters because her hymn shows how Greeks call chthonic powers

In the hymn, the speaker does three very specific things:

- They call the deity by name, twice

- They use incense / breath / smoke

- They address her directly as an awe inspiring (σαβου) earth-mother power (χθονίη)

That is exactly the kind of speech happening in the cross-cry if you stay inside Greek ritual logic.

Hipta is important because her hymn preserves the grammar of chthonic calling.

The Repeated name

- Ἵππας — name spoken alone (invocation)

- Ἵππαν κικλήσκω — “Hipta I call”

- χθονίη μήτηρ, βασίλεια — vocatives layered on top

This is serial address, not narration.

The invocation logic is:

- name → name again in calling verb → epithets in vocative

- Address → intensification → address

That is exactly the same functional move as:

- Ἐλωΐ Ἐλωΐ

Saba

When Proclus writes:

μυστιπόλον τελετῇσιν ἀγαλλομένην Σάβου ἁγνοῦ

he shows that Σάβου / Saba- belongs to:

- initiation (τελετή)

- ritual joy / ecstasy

- incense and breath

- chthonic-oriented rites

So when you hear σαβα-χθαν-ίη, the Greek ear already knows:

“This is the sound used when calling an awe inspiring earth-mother power in a rite.”

Hipta gives us the dictionary of ritual behavior, and

She shows us what kind of utterance this is.

That’s why she’s relevant.

The cry

this line is not a saying.

It’s not a teaching.

It’s not a parable.

It’s not dialogue.

It’s a φωνή (phone) — a vocal event.

Greek authors only preserve those when:

- the sound mattered

- the moment mattered

- the meaning wasn’t propositional

That’s why only Mark preserves it first, and Matthew copies it.

Luke and John avoid it entirely — which tells you ancient authors already found it awkward to interpret, not easy to explain.

Saba (σαβα)

σαβα is not a word by itself.

It is a sound-cluster that belongs to Greek ritual language.

When Ancient Greeks hear σαβα-, they think:

- shaking bodies

- trance

- ecstatic movement

- awe that overwhelms the body

- initiation rites

That comes straight from σαβάζω (shake violently) and σέβας (reverential awe).

Same sound family. Same cultic space.

σαβάζω (shake violently)

σέβας (reverential awe)

A.“σέβη” A. Supp.755, as if from σέβος, τό: (σέβομαι):—reverential awe, which prevents one from doing something disgraceful (cf. σέβομαι)“, ς. δέ σε θυμὸν ἱκέσθω Πάτροκλον Τρῳῇσι κυσὶν μέλπηθρα γενέσθαι” Il.18.178; “αἰδώς τε ς. τε” h.Cer.190; also awe with a notion of wonder, “ς. μ᾽ ἔχει εἰσορόωντα” Od.3.123, 4.75, cf. 142, etc.: generally, reverence, worship, honour, “ς. ἀφίσταται” A.Ch.54 (lyr.); “ς. τὸ πρὸς θεῶν” Id.Supp.396 (lyr.): c. gen. objecti, Διὸς σέβας reverence for him, Id.Ch.645 (lyr.): c. gen. subjecti, “πάγος ἄρειος, ἐν δὲ τῷ ς. ἀστῶν” Id.Eu.690; so εἰ. περ ἴσχει Ζεὺς ἔτ᾽ ἐξ ἐμοῦ ς. S.Ant.304.

II. after Hom., the object of reverential awe, holiness, majesty, “ς. Τροΐας” Sapph.Supp.5.9; “δαιμόνων ς.” A.Supp. 85 (lyr.); γᾶ, πάνδικον ς. ib.776 (lyr.); θεῶν σέβη ib.755, cf. E.Med.752; Ἥλιε, . . Θρῃξὶ πρέσβιστον ς. (as Bothe and Lob. for σέλας) S.Fr.582; ς. ἐμ<*>πόρων, of a funeral mound serving as a land-mark, E.Alc.999 (lyr.): hence periphr. of reverend persons, ὦ μητρὸς ἐμῆς ς. A.Pr.1091 (anap.); ς. κηρύκων, of Hermes, Id.Ag.515; “ς. ὦ δέσποτ᾽” Id.Ch.157 (lyr.), cf. E.IA633; Πειθοῦς ς. A.Eu.885; τοκέων ς. ib.546 (lyr.); Ζηνὸς ς. S.Ph.1289; of things, “ς. μηρῶν” A.Fr.135; “χειρός” E.Hipp. 335; “ς. ἀρρήτων ἱερῶν” Ar.Nu.302.2. object of awestruck wonder, “ς. πᾶσιν ἰδέσθαι” h.Cer.10: πᾶσι τοῖς ἐκεῖ σέβας, of Orestes, S.El.685; of the arms of Achilles, Id.Ph.402 (lyr.).

euai/euoi (εὐαῖ/εὐοῖ) - the bacchic shout directly references sabai (σαβαῖ)

εὐαῖ (εὐαἳ Hdn. Gr.1.503), a cry of joy like εὐοῖ, Ar.Lys. 1294 (lyr.), etc.; εὐαῖ σαβαῖ Eup.84.

εὐοῖ (εὐοἳ A.D.Synt. 320.1, cf. Lat. euhoe), exclamation used in the cult of Dionysus, Ar. Lys. 1 294 (lyr.), etc.; cf. εὐαῖ, εὐάν: εὐοῖ σαβοῖ D. 18.260 : as an interjection, ἀναταράσσει—εὐοῖ—μ᾽ ὁ κισσός S. Tr.219 (lyr.).

sabai (σαβαι) - another bacchic cry, like euai/euoi:

σαβαῖ, a Bacchanalian cry, like εὐαί, εὐοῖ, Eupol. Βαπτ. ΙΟ.

sabadzios (σαβάζιος) - essentially this is Bacchus / Dionysus

— a Phrygian–Thracian ecstatic deity, closely assimilated to Dionysus in Greek sources; his rites and mysteries were understood by Greeks as functionally equivalent to Dionysiac teletai (τελεταί), involving possession, ritual cries, and initiatory ecstasy.

A.“θεῷ Σαβαζίῳ παγκοιράνῳ” CIG3791 (Bithynia), cf. IG12(5).27 (Sicinus); “Δὶ Σαβαζίῳ” BMus.Inscr.1100 (Italy, iii A.D.); Διὶ

- Sabázios (Σαβάζιος) - means bacchus (who is the roman version of greek dionysis). A figure who represents ecstasy and reverential awe.

So that we understand where saba (σαβα) "awe" comes from, it's bacchic.

So saba (σαβα) means something like:

“ecstatic awe”

“ritual shaking”

“initiation-force”

Not as a sentence. As a felt state.

“giving someone Saba” means to initiate them.

Think of inhaling the smoke from (herbal) sacrifice or incense.

Sabaoth (σαβαωθ) - previous use is seen in the PGM as a ritual incantation

This PGM rite / incantation seems related to whatever was happening in the garden of Gethsemenie (we have another gumnos boy with a sindon).

Ἄλλο πρὸς Ἥλιον·

παῖδα γυμνὸν περιτύλιξον σινδόνινον ἀπὸ κεφαλῆς ἄχρι ποδῶν, καὶ κρότησον ταῖς χερσίν· ποιήσας δὲ ψόφον, στῆσον τὸν παῖδα κατέναντι τοῦ ἡλίου, καὶ σὺ ὄπισθεν αὐτοῦ σταθεὶς λέγε τὸν λόγον·

Ἐγώ εἰμι Βαρβαριώθ· Βαρβαριώθ εἰμι· Πεσκουτ Ἰαω Ἀδωναΐ Ἐλωαὶ Σαβαώθ, εἴσελθε εἰς τὸ παιδάριον τοῦτο σήμερον· ἐγὼ γάρ εἰμι Βαρβαριώθ.

Another," to Helios: Wrap a naked boy in fine medical linen bandage from head to toe, then clap your hands. After making a ringing noise, place the boy opposite the Helios, and standing behind him say the formula:Here we see an older rite involving same elements

"I am Barbarioth; Barbarioth am I; PESKOUT YAHO ADONAI ELÕAI SABAÕTH, come in to this little one today, for I am Barbarioth."

Tr.: W. C. Grese and Marvin W. Meycr (Coptic sections, II. 91-93).

- gumnon (γυμνὸν) - naked

- sindoninon (σινδόνινον) - fine linen surgical grade bandage

- paida (παῖδα) - child; (and in this context, a young immature boy)

- Different word than neaniskos, same age range overlap.

- elouai sabaouth (Ἐλωαὶ Σαβαώθ) - same phoneme sounds as what was spoken on the cross with "eloui eloui lama sabachthani".

We see sabaouth (σαβαωθ) in other non-christian texts, like this PGM ritual incantation above.

sabaouth (σαβαώθ, τό) - related to the saba cluster:

- sabai (σαβαί, ἡ) - Bacchic acclamation; ritual shout in Dionysiac/Sabazian rites.

- sabadzou (σαβαδάζω) - shake violently

- sebas (σέβας) - reverential awe, awestruck wonder

- Sabazios (Σαβάζιος) - a Phrygian–Thracian god assimilated to Dionysos in Greek ritual culture. Sabazios rites involve ecstasy, possession, snakes, initiation.

- The -ωθ ending sonically thickens, as a field of power, the sabadzou violent shaking sebas awestruck sabai cry to Sabazios Bacchus.

This could make the case for different segmentation, than saba chthani:

elouai elouai lama sabaouth ani

Chthonie (χθονίη)

Now χθονίη (chthonie).

This one is a real grammatical word.

It means:

“O one of the earth”

“O chthonic mother”

“You who belong below”

You say χθονίη when you are calling an earth-power directly.

- χθονίη (chthonie) means “she of the earth.” Afterall, Sophia was the goddess of the earth, and Gaia (Earth) was feminine, while Ouranous (Heaven) was masculine. If you look at the Atticized variant of Hipta’s hymn, you’ll see χθονία (chthonia) instead. What’s cool about the Koine form here is that it brings the hymn back into direct address. When speaking to “chthonia” directly, you would say “chthonie.”

Saba (σαβα) Cthonie (χθονίη)

Now put them together:

σαβα χθονίη

Not a sentence.

Not grammar.

A call.

It means:

“Ecstatic, awe-bringing one of the earth”

“O chthonic power of initiation and shaking”

“O earth-mother who brings trance and descent”

Like a child yelling:

“Big scary mom of the ground!”

Not explaining. Calling.

saba chthanie (σαβα χθανίη)

σαβα χθανί — which we restore to σαβα χθανίη once the dying breath is accounted for. The trailing vowel is fading; the scribe hears something, not a clean ending, and later editors slap a question mark on it. But Greek manuscripts originally had no question marks, and Greek ritual speech does not invoke by asking questions.

Phonetically restored, σαβα χθανίη aligns with cultic sound-forms connected to Σάβου / Σάβα, which in Greek ritual language is about awe / shaking / initiation force. LSJ under σεβάζω gives the core sense as “to make sacred, to initiate with reverent awe.” Exactly the register Proclus preserves when he writes of Hipta, the chthonic mother, approached through incense and nocturnal rites.

Now connect this back to the cross-cry.

When you hear σαβαχθανίη, what the Greek ear hears is:

- σαβα- → ecstatic ritual awe / shaking / initiation force

- χθαν- → chthonic / earth / below

- -ίη → direct address (“O you!”)

So the meaning is not “why”.

The meaning is:

Calling out to a chthonic initiatory power as life leaves the body

That is why:

- the breath fades

- the ending vowel blurs

- the scribe writes sound, not grammar

- later editors panic and invent a question

Heli Heli, Eloui Eloui, Euoi Euoi

Mark says: Ἐλωΐ Ἐλωΐ λαμὰ σαβαχθανί

Matthew says: Ἡλί Ἡλί λεμὰ σαβαχθανί

- [Name], [Name] → direct vocative address, intensified by repetition, repeated as we saw in Hipta invocation

Name:

- heli (ἡλί) — phonetic shortening of Ἥλιε — vocative of Helios

- eloui (ἐλωΐ) — scribal attempt to capture an unstable vowel cluster, possibly indicates Heli again, or

- euoi (εὐοῖ) — the bacchic cry of life (see next section)

euoi euoi - the bacchic cry of life

Mark says: Ἐλωΐ Ἐλωΐ λαμὰ σαβαχθανί

Matthew says: Ἡλί Ἡλί λεμὰ σαβαχθανί

Considering that this text is phonemic (sounded out, what people heard) rather than vocabulary, it could easily be "euai euai"

- also realize, that the cult hasn't been informed of the bacchic nature.

- Jesus is coopting a previous bacchic tradition in order to spin up a new cult.

- Those who heard his words on the cross would not understand the Greek.

We know that the Eua, that boethos (battle partner) in initiatory battle, makes a bacchic shout euoi (εὐοῖ εὐοῖ) to Zoe (ζωή - animated life force).

So, Jesus could be invoking the Bacchic shout here, rather than Prophet Elias, or Sun God Helios. Bacchic shout fits really well with the other greek words here.

A.cry εὐαί, in honour of Bacchus, S.Ant.1134 (lyr.), E.Ba. 1034 (lyr.); “Διονύσῳ” AP9.363.11 (Mel.), cf. D.S.4.3, Callistr.Stat.2: c. acc. cogn., “μελῳδὸν εὐ. χορόν” Sopat.10:—Med., “Βάκχιον -ομένα” E. Ba.68 (lyr.).

- euoi (εὐοῖ) - Dionysian / Bacchic invocation (for a Bacchic rite)

Invocations are often repeated twice in magic incantations.

sabai - saba revisited, another Bacchanalian cry, like euoi

There's bacchus all over these words, here's another possibility

σαβαῖ, a Bacchanalian cry, like euai (εὐαί), euai (εὐαί), Eupol. Βαπτ. ΙΟ.

- Bacchic cries are not fixed lexical words — they are φωνήματα (vocalizations).

- Lexica record how authors wrote the sound, not a single “correct spelling.”

- σαβαῖ, εὐαί, εὐοῖ are treated by ancient lexica as equivalent cries, not etymological derivatives

lama/λαμὰ or lema/λεμὰ

A.will, desire, purpose, Epich.182 (prob.l.): concrete, λ. Κορωνίδος wilful Coronis, Pi.P.3.25; μητρῷον λ. thy proud mother, S.El.1427; λήματος κάκη weakness of will, cowardice, A.Th.616; “ἥκιστα τοὐμὸν λ. ἔφυ τυραννικόν” E.Med.348; “ἐς τὸ κέρδος λ. ἔχων ἀνειμένον” Id.Heracl.3, cf. 199, Alc.981 (lyr.), Ba.1000 (lyr.).

II. temper of mind, spirit, either,1. in good sense, courage, resolution, “εὔτολμον ψυχῆς λ.” Simon.140; “γενναῖον λ.” Pi.P. 8.45, cf. N.1.57; αἴθων λ. fiery in courage, A.Th.448; “δύο λήμασιν ἴσους Ἀτρεΐδας” Id.Ag.122 (lyr.); τοξουλκῷ λήματι πιστοί relying on their archer spirit, Id.Pers.55 (anap.); “ἀρείφατον λ.” Id.Fr.147; “πέτρας τὸ λ. κἀδάμαντος” E.Cyc.596; “λ. οὐκ ἄτολμον” Ar.Nu.457 (lyr.); “καθ᾽ Ἡρακλέα . . τὸ λ. ἔχων” Id.Ra.463; or,

2. in bad sense, insolence, arrogance, audacity, “ὅσον λ. ἔχων ἀφίκου” S.OC877 (lyr.); ὦ λῆμ᾽ ἀναιδές ib.960; “δῆλον . . τἀνθρώπου᾽ στι τὸ λῆμα” Ar.Nu.1350 (lyr.).— Poet. word, also used in Ion. Prose, in signf. spirit, courage, “ἔργα χειρῶν τε καὶ λήματος” Hdt.5.72; λήματος πλέος ib.111, cf. 7.99, 9.62: and in late Prose, as D.S.2.58 (pl.), J.BJ3.10.4, Luc.Dem.Enc.50, etc.; defined by Andronic.Pass.p.575 M.

And we see from the lexicon that λᾶμα means λῆμα anyways...

Bottom Line, lama means:

- lama (λᾶμα) - will, desire, purpose

Codex Vaticanus gives dzabaphoane (or phthane)

Codex Vaticanus contains one of the earliest known text of the Greek New Testament.

- There are also other earlier fragments available as well.

Take a look.

Early text contained no spaces, which does give us liberty of segmentation.

ελωι ελωι λαμα ζαβα φοανε (or φθανε)

eloui eloui lama dzaba phoane (or phthane)

Taken phonetically, there's no reason this couldn't also be saba cthanie.

But let's analyze what it could be in the Greek

ζαβα in the lexicon

I. intr. to make a stride, walk or stand with the legs apart, Lat. divaricari, εν διαβάς of a man planting himself firmly for fighting... (cutting it off here, there's more) ...

II. ...2. ... to cross over, like Lat. trajicere ...

LSJ lexicon is similar:

A.“ζάβαις” Alc.Supp. 7.3:

I. intr., stride, walk or stand with legs apart, εὖ διαβάς, of a man planting himself firmly for fighting, Il.12.458, Tyrt.11.21; “ὡδὶ διαβάς” Ar.V.688; “τοσόνδε βῆμα διαβεβηκότος” Id.Eq.77; opp. συμβεβηκώς, X.Eq.1.14; “πόδας μὴ -βεβῶτας” Hp.Art.43, cf. D.S.4.76; “κολοσσοὶ -βεβηκότες” Plu.2.779f; simply, spacious, “δόμοι” Corn.ND 15: metaph., μεγάλα δ. ἐπί τινα to go with huge strides against . ., Luc. Anach.32; ὀνόματα -βεβηκότα εἰς πλάτος great straddling words, D.H. Comp.22; [ποὺς] -βεβηκώς with a mighty stride, ib.17: c. acc. cogn., αἱ ἁρμονίαι διαβεβήκασι εὐμεγέθεις διαβάσεις ib.20; also “ἐξερείσματα χρόνων πρὸς ἑδραῖον -βεβηκότα μέγεθος” Longin.40.4.

II. c. acc., step across, pass over, “τάφρον” Il.12.50; “πόρον᾽ Ωκεανοῖο” Hes. Th.292, cf. A. Pers.865 (lyr.); “Ἀχέροντα” Alc. l.c.; “ποταμόν” Hdt.1.75, etc., cf. 7.35; also “διὰ ποταμοῦ” X.An.4.8.2.2. abs. (θάλασσαν or ποταμόν being omitted), cross over, “Ἤλιδ᾽ ἐς εὐρύχορον διαβήμεναι” Od.4.635; “<ἐς> τήνδε τὴν ἤπειρον” Hdt.4.118; “πλοίῳ” Id.1.186, cf. Th.1.114, Pl.Phdr. 229c, etc.: metaph., τῷ λόγῳ διέβαινε ἐς Εὐρυβιάδεα he went over to him, Hdt.8.62; “δ. ἐπὶ τὰ μείζω” Arr.Epict.1.18.18.b. πόθεν . . διαβέβηκε τὸ ἀργύριον from what sources the money has mounted up, Plu.2.829e.3. bestride, AP5.54 (Diosc.).

4. decide, “δίκας” SIG426.7 (Teos, iii B. C.).

5. come home to, affect, “εἴς τινα” Diog. Oen.2, Steph. in Rh.281.5.

- dzaba (ζαβα) - from dzabatos (ζάβατος) which is Aeolic for diabatos (διαβατός) - crossed/passed (to transfer); planting himself firmly for fighting

- a truncated phonetic string

- dzaba is perhaps weak grammatically, but he's putting up a fight, which seems to be in the spirit of the scene.

phoane (φοανε) may refer to φημί here:

I.Radical sense: to declare, make known;

II.Special Phrases:1.φασί, they say, it is said,III.in a more definite sense, like κατάφημι, to say yes, affirm

- phoane (φοανε) possibilities:

- phoune (φωνή) — voice, sound, utterance

- phounaou (φωνάω) — cry out

- might come from phay-mi (φημι) which means "to affirm"

- dzaba phoane (ζαβα φοανε) - "planted firmly for fighting, I say/I cry out/it is said".

Or perhaps that text has a faded theta "θ" not omicron "ο"

- phthane (φθανε/φθάνω) = to arrive first, get ahead of, anticipate

- dzaba phthane (ζαβα φθανε) - "planted firmly for fighting, anticipated".

dzaba is perhaps weak grammatically, but he's putting up a fight, which seems to be in the spirit of the scene.

chthani (χθανί) is also very close in sound to phoane (φοανε), compare:

- chthani (χθανί) - heh-thah-nih

- phthane (φθανε) - fah-thah-neh

- phoane (φοανε) - fah-ah-neh (f and th sound similarly breathy; tha and fah similar sounds)

- heh-thah-nih vs fah-ah-neh are very similar sound utterances. All three match each other closely

NOTE: zaba phoane (or phthane) seems to have been corrected to saba chthani, in later versions, it's worth asking why.

Final, dead simple version

Reminder:

Matthew says: Ἡλί Ἡλί λεμὰ σαβαχθανί

here's a methodologically sound phoneme-vocalization-mapping (φωνήματα) to actual Greek words:

euai euai lama sabai chthanie

Euai! Euai! — with intent — Sabai! — O chthonic woman!

more literally:

[cry in honor of Bacchus]! [cry in honor of Bacchus]! - with driving intent - [cry of ecstatic vitality / Bacchic animation]! o chthonic woman!

euai euai lama dzaba phoane

[cry in honor of Bacchus]! [cry in honor of Bacchus]! - with driving intent - planted firmly for fighting, I say!

- euai euai (εὐαί εὐαί) - a cry/shout in honor of Bacchus (double invocation common in incantation)

- alt: heli heli (ηλι ηλι) - invoking helios, "divine light" or unity mind

- lama (λᾶμα) - will, desire, purpose (lama (λᾶμα) refers to lema (λῆμα) in the lexicon)

- saba (σέβας, σαβάζω) - initiatory awe, shaking / trance

- synonym: sabai (σαβαῖ) - Bacchanalian cry of life

- alt: dzaba (ζαβα) - from dzabatos (ζάβατος) which is Aeolic for diabatos (διαβατός) - planted firmly for fighting

- chthanie (χθανίη) - O chthonic one, she of the earth

- could be reference to Hipta or Gaia, who have roles at the moment of descent, in death/resurrection rites

- phoane (φοανε) - I say! (If it's an omicron)

- phthane (φθανε) - anticipated (if it's a theta)

This might shatter your world:

He is calling.

He is calling a chthonic initiatory power associated with:

- euai euai (εὐαί εὐαί) - invoking the cry to honor bacchus

- alt: heli heli (ηλι ηλι) - invoking helios, "divine light" or unity mind

- λῆμα (λῆμα) - will, desire, purpose (λᾶμα refers to λῆμα in the lexicon)

- saba (σέβας, σαβάζω) - initiatory awe, shaking / trance

- synonym: sabai (σαβαῖ) - Bacchanalian cry of ecstatic vitality / lifeforce animation

- chthanie (χθονίη) - “O chthonic one, she of the earth” (feminine, singular, vocative)

- could be reference to Hipta or Gaia, who have roles at the moment of descent, in death/resurrection rites

"to bacchus! to bacchus! with intent, Awe! O chthonic feminine"

And the words sound broken because the breath is breaking.

That’s it.

That’s the whole thing.

Jesus was making an invocation to the earth mother, who brings initiatory shaking awe and descent into trance.

“Ecstatic, awe-bringing one of the earth”

“O chthonic power of initiation and shaking”

“O earth-mother who brings trance and descent”

This is the shout of a bacchant who is performing the mystery

What's crazy is that he got himself killed while performing the mystery itself.

He was supposed to enter "into death", and then come out in "ressurection", but his boy got clipped, and he ended up dazed on a cross, screaming out bacchic implications to the god.

Bottom Line

Gaia is the cthonic mother

Hipta is the one who helps during Gaian descent

And Jesus was calling to the cthonic mother by invoking the saba chthonie - the awe inspiring ecstacy-inducing chthonic woman

In Orphic Cosmology

As we see in Orphic Cosmology a structure that exists in Genesis

- The cthonic mother, Gaia is the lower "fear mind"

- Ouranos is the ordered or "divine" mind...

- And initiatory Fire forges the initiate by suppressing their Gaia mind, so that they can reform as Ouranic mind...

- Helios here might allude to solar consciousness, clarity, unity, to that Ouranic state

Hipta and Gaia are the same functional cthonic Mother seen at different depths of the rite.

- Gaia = cosmological ground, fear-mind substrate

- Hipta = Gaia as experienced during descent

- the same chthonic function is encountered phenomenologically under different names depending on where the initiate is in the rite

Gaia = structural / cosmological layer

Gaia in Orphic cosmology functions as:

- the ground of psyche

- the substrate of fear, attachment, embodiment

- the Titanic layer prior to ordering

She is always present, but usually not felt consciously.

Hipta = experiential / descent layer

Hipta is manefested only when Gaia becomes subjectively overwhelming:

- during ego dissolution

- during panic, enclosure, falling, being “taken down”

- at the threshold of unconsciousness or ritual death

Spoken before unconsciousness or ritual “death,” “Helios, Helios—awe! O chthonic Mother!” reads less like prayer and more like a diagnostic utterance: the initiate naming the forces currently acting upon the psyche as it is being dismantled and reforged. Right before coma.

Read within Orphic initiatory cosmology, the phrase compresses the entire Orphic rite into a single breath.

- see Orphic Cosmology for background

Alternate translations

There's a few ways to chop it up, all more or less imply the same thing.σαβαχθανί (with possible fading vowel)

- dzaba phoane - "stand with affirmation" - supports the bachic cry, euoi euoi

- Sabadzthana == Sabadz(ios) Thana(tos) (Σαβάζιος θανατος) - your dead Sabazios (saba-Zeus, or Dionysus)

- σαβαχ = Sabadz(ou) (Σαβάζιος) - could be related to Σαβάζιος (Sabazios), the Thracian and Phrygian god of ecstasy, fertility, and wine, often syncretized with Dionysus

- σαβάζω - from the polaskian side, from the kolchis era. comes this saba root. Long before any sumerian. (see Septuagint VS Masoretic Text - 100K Subs - Ammon Hillman Kipp Davis Mythvision - Gnostic Informant

- θανί = Thana(tos) (θανατος) - death

- Under extreme stress or fading death:

- sabadz (Σαβάζ) could easily sound like sabach (σαβαχ) to the listener, under slurring it's plausible that ζ (dz or z - th sibilant) could easily sound like χ (ch - k fricative) depending on the language pronunciation of the time.

- thana (a = ah as in father) sounds a lot like thani (i = ih as in sit), under slurring, it's plausible.

- those trailing letters in () could be weakened voice or slurring in the moment of death.

- σαβαχ = Sabadz(ou) (Σαβάζιος) - could be related to Σαβάζιος (Sabazios), the Thracian and Phrygian god of ecstasy, fertility, and wine, often syncretized with Dionysus

- Sa Bach Thani (Σα βάχ θανι) - your dead Bacchus

- σαβαχ = Sa Bach (Σα βάχ) - could be related to Βάκχος (Bacchus), the Dionysian god of ecstasy, fertility, and wine

- θανί = Thani (θανι) - death

- Saba chthoni (σαβα χθανι) - your cthonic host

- σαβα = Saba (σαβα) - host

- χθανί = Chthani (χθανι) - cthonic/earth realm

- Dzaba phoane (ζαβα φοανε) - "planted firmly for fighting, I say!"

- Dzaba (ζαβα) - "planted firmly for fighting"

- phoane (φοανε) - "I say!"

- Dzaba phoane (ζαβα φοανε) - "planted firmly for fighting, anticipated"

- Dzaba (ζαβα) - "planted firmly for fighting"

- phthane (φθανε) - "anticipated"

The Possible: zaba phoane (ζαβα φοανε), zaba is perhaps weak grammatically, but he's putting up a fight, which seems to be in the spirit of the scene.

The Good: Below, saba chthonie (σαβα χθανιη) here works linguistically:

- Saba chthonie (σαβα χθανιη) - O chthonic/earth-mother of initiatory awe and shaking

- σαβα = Saba (σαβα/σάβου) - initiatory shaking ecstatic awe during the descent into trance

- χθανί(η) = Chthanie (χθανιη) - cthonic/earth goddess

Only one solid option. But those other 3 options sound directionally similar.

So we have some alignment!