Old Testament Greek Origins

TODO: bring over more references from the livestream notes

- Timeline

- Hebrew Timeline

- Introduction

- The Letter of Aristeas

- Stylistic Linguistic Evidence from Dr Hillman

- Hebrew, Isreal, and Judean terms don't appear until they need to

- Ἑβραῖος / Ἑβραῖοι (Hebrews)

- Ἰσραήλ / Ἰσραηλίτης (Israel)

- Ἰουδαῖος / Ἰουδαία (Judean, Jews)

- Hecataeus of Abdera

- Josephus (1st c. CE)

- Origen and Christian apologists (2nd–3rd c. CE)

- Earliest uncontested Greek appearance: the Septuagint (c. 290–250 BCE)

- Does this support a hypothesis of “Priesthood War / Anti-Echidnaic Propaganda”?

- Bottom Line

- what about earlier Egyptian text?

- what about earlier Persian text?

- any other references?

- Technical Precision of Greek - According to Lucretius

- Julius Africanus

- Porphyry - these books, they’re not written in Hebrew

- Gad Barnea at U of Haifa

- Ketef Hinnom scrolls

- Paleo Hebrew is actually Phoenician

- Any older Hebrew fragments are just liturgical fragments

- Ketef Hinnom Silver Scrolls (c. 650–587 BCE)

- Lachish Letters (Ostraca) (c. 588 BCE)

- Siloam Tunnel Inscription (c. 701 BCE)

- Gezer Calendar (c. 925 BCE)

- Tel Zayit Abecedary (Zayit Stone) (10th c. BCE)

- Khirbet Qeiyafa Inscription & Others (11th–10th c. BCE)

- Other Paleo‐Hebrew Inscriptions from 8th–7th c. BCE

- Miscellaneous Script Evidence

- Proto-Literary Hebrew Content Pre-270 BCE

- Greek New Testament quotes the Greek concepts from the Greek Septuagint not from the Hebrew versions

- The Greek was the authoritative source until the 400CE Latin Vulgate

- Hebrew was dead by 400BCE

- Many features of Biblical Hebrew do look like stylized, reduced, and semiticized versions of structures from Classical and Hellenistic Greek.

- There was No Hebrew Libraries or Literature before ~250BCE

- The Documentary Hypothesis is Flawed - this is how Hebrew was ever dated to 10th BCE

- No Hebrew manuscripts predating the Septuagint exist.

- Stylistic Analysis from Complexity - Hebrew is coarse concrete vs Greek nuanced advanced technical abstract

- The Septuagint and Atticizing Tendencies

- Elephantine Papyri

- Scholarly Support

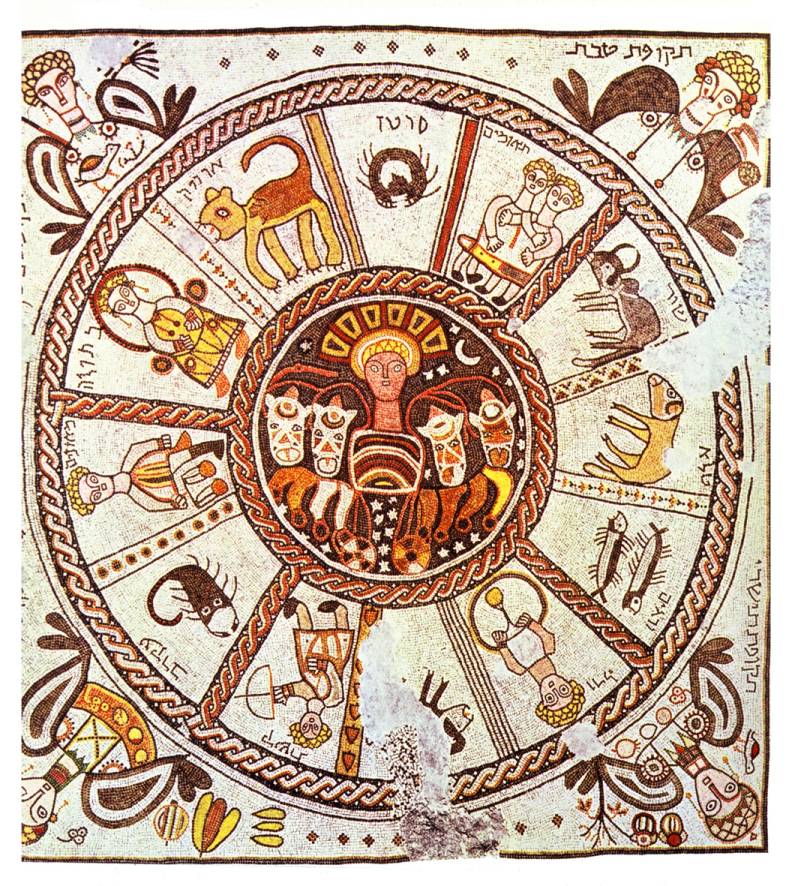

- There was Greek in ancient synagogues

- Specific word examples

- Musterion vs Hidden

- Argument from Technical Detail

- The Physics of Genesis are Greek Physics

- Hebrew is Greek - Joseph Yahuda

- Alleged Greek transliterations of ancient Hebrew

- Paleo Hebrew is Coarse Language - 3rd Grade - Supporting concrete but not abstract thought

- Conclusion

- Does it really matter what language was first for the Old Testament?

Timeline

The oldest canonical Old Testament we have evidence of, comes to us via the Greek language.

- Before ~300BCE (no earlier Old Testament books are known)

- No earlier Old Testament manuscript evidence exists than the Greek Septuagint LXX books and chapters in the Greek language...

- There is no known Hebrew long form literature before this time.

- There are Hebrew minor short inscriptions or short blessings occasionally included into Septuagint books/chapters (see below).

- Hebrew was also a dead language by 400BCE, with severe language limitations, at a 3rd grade level. (see below)

- 290-250BCE - Septuagint LXX (Koine Greek with Atticisims - Alexandria, Egypt)

- mixture of three different manuscripts: codex vaticanus, codex sinaiticus, and the Codex Alexandrakis

- the Septuagint (LXX) shows clear layers of Greek style, and many scholars note that certain books or passages are “Atticizing” or show influence from Attic Greek norms, even though the language is fundamentally Koine Greek.

- Certain books show Attic vocabulary, syntax, and stylistic traits. e.g. Job and Isaiah in the Septuagint are often singled out as showing strong Atticizing tendencies

- 250-68BCE - Dead Sea Scrolls (Paleo-Hebrew, Aramaic, and Koine Greek)

- Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered in the Qumran Caves in the West Bank between 1946 and 1956.

- discovered in caves near Khirbet Qumran, on the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea. While the exact authorship is debated, many scholars believe the scrolls were written by a Jewish sect, potentially the Essenes, who inhabited a settlement at Qumran

- Contains both Hebrew and Greek fragments

- Hebrew makes up 85% of the scrolls

- Aramaic makes up about 13%

- Greek comprises around 2%

- Simplified

- Simplified Hebrew is based on Septuagint Greek from ~300BCE.

- Hebrew at this time has ~7000 words, while the Greek has ~1.5M words, so simplification was nessesary. Hebrew was a dead language, and much lower resolution technically.

- The Greek fragments also simplified. (as if back translated from the simple Hebrew)

- The Greek appears to be a back-translation from the Proto Hebrew translation, for a propaganda campaign by the Qumran sect, to own those previous texts for their cult.

- Conclusion: The Qumran cult converts original Greek Old Testament (Septuagint) to a much simplified Hebrew (8000words in Paleo-Hebrew, 1.6M in Ancient Greek, Hebrew is dead language by 400BCE this point). Which loses all nuance and Hellenic context found in the earlier Greek Septuagint (LXX). It contains both Greek (back-translated from Hebrew) and Hebrew (translated from the original Greek). Attempt to resurrect the dead Hebrew language for the extremist cult to co-opt and own the Greek language rabbinical work for their extremist sect. Simplification and Hebrewification towards a narrative of owning the text for the strength of the cult. The scrolls were written in Paleo-Hebrew, Aramaic, and Koine Greek. The scrolls were written on parchment, papyrus, and bronze. The scrolls were created by Jewish extremists that lived in Qumran until the Romans destroyed the settlement around 70 CE. The scrolls are also known as the Qumran Caves Scrolls. A mix of Paleo-Hebrew (for some texts like parts of Leviticus) and the square Aramaic script (proto-Masoretic and Qumran script styles).

- 70-120CE - New Testament heavily refers to Greek Language Septuagint, not the Hebrew

- 200-400CE - Nag Hammadi (Sahidic Coptic)

- The Nag Hammadi Codices were discovered in 1945.

- Sahidic Coptic, a late form of the Egyptian language. While the texts are in Coptic, they are believed to be translations of works originally written in Greek

- 400CE - Latin Vulgate derived from village Hebrew copies and using Greek to fill in missing parts (Hebrew likely a back translation from the Greek), is now used as official text of new Roman Catholic Theocracy (official theocratic government).

- Greek was the standard until this point in time. (~300 years!)

- Orthodox Christianity continues using Greek however, to this day (they never switched away).

- 7-10th century CE - Masoretic text was written (Medieval Hebrew)

- Using the Medieval Hebrew language that existed from the 6th to the 13th century CE, when Hebrew borrowed words from other languages.

- ~930 CE - Aleppo Codex (Medieval Hebrew)

- Earliest complete Pentateuch in Hebrew. Parts are missing now. When Hebrew borrowed words from other languages.

- 1155CE - Talmud (Medieval Hebrew)

- Using the Medieval Hebrew language that existed from the 6th to the 13th century CE, when Hebrew borrowed words from other languages.

Hebrew Timeline

The history of the Hebrew language is usually divided into four major periods:

- Before 3rd century - Biblical (Classical) Hebrew. Before this time, There is no archaeological or manuscript evidence of Bible text, literature or libraries other than: inscription, amulet, or short blessings. All evidence for earlier dating comes from a "Document Hypothesis" formed in 1866-1880CE by Karl Heinrich Graf & Julius Wellhausen

- 200CE - Mishnaic, or Rabbinic, Hebrew, the language of the Mishna (a collection of Jewish traditions), this form of Hebrew was never used among the people as a spoken language.

- 200-400CE Tiberian or Proto-Masoretic is inferred here... and also never spoken.

- 390CE Jerome changes the Latin Vulgate Bible from being based on the Greek, which was standard up to this point and what the Christian Apostles used, to based on Hebrew, pulled from surrounding communities. The Hebrew Jerome used ≈ Proto-Masoretic / Tiberian scribal Hebrew (not spoken), codified between about 2nd–5th century CE. no Hebrew manuscript from Jerome’s own time has survived intact, all timeline is inferred, evidence chain for the language is biblical only, no other literature exists.

- 6-13th cent CE - Medieval or Masoretic Hebrew, when many words were borrowed from Greek, Spanish, Arabic, and other languages. Used to create the Masoretic text.

- 930 CE (Codex Aleppo), 1008 CE (Codex Leningradensis) - Masoretic text was first published.

- 1920-1948 - Modern Hebrew, the language of Israel today. By 1913–1920, Modern Hebrew had standardized grammar and vocabulary, and by 1948, it was officially the language of the State of Israel. The movement was led primarily by Eliezer Ben-Yehuda (1881–1922), who believed Hebrew should become a living, spoken national language for Jews returning to Palestine. Some returns (~60k) happened 1882-1914, then 1948 after WWII and the new Isreal state, 100's of 1000's migrated and this language was made official for the new country. Modern Hebrew’s vocabulary is about half biblical revival and half modern adaptation from surrounding tongues.

Introduction

We're talking about the Greek Language, not the Greek country. We're talking about the language origin of the Old Testament.

The Greek Language Septuagint (LXX) is the original and foundational Old Testament text, alleged to have been written in Greek by a group of 72 rabbis from Crete who harbored disdain for the female tyrants and oppressors of neighboring lands (the Medes, the civilization of Medea; such as the oracular justice system by the Parthenos ). This Greek Septuagint was rich in philosophical and mystical concepts derived from the pre-Hellenic Bronze Age, rooted in the drug/divining/medicine culture that was dominant at the time. These scholars drew upon a broad knowledge of mystical philosophy, myth, and metaphysics, embedding the sophisticated concepts of the region’s Bronze Age Greek, Mycenaean, Minoan, and Medean cultures into the original Greek text.

Ancient Hebrew, however, is not the root language of these texts. Instead, it was a later, constructed form—a fabricated language developed by an extremist sect seeking to consolidate power, gain control over the religious narrative, and reshape the people’s connection to divinity. This sect, operating under a cult-like agenda, recognized the power and descriptive richness of the original Greek scriptures, but sought to downplay the profound nuances of the Greek Septuagint in favor of a much more simplistic and rigid Hebrew. This movement effectively drove out any references to pharmaka (the substances related to seeing, divining, healing, and spiritual experiences), replacing them with vague and fantastical terms like “magic” or “sorcery,” which obscured the deeper connections to drug-induced divination and the spiritual practices of the time.

The key driving force behind this movement was the creation of a version of the text that replaced the "reality" (pharmaka and cognitive practices) with the "fairy tale" (supernatural) that is more dogmatic, and more easily commands the control of people, disarming critical thinking. In a nutshell it replaces Greek Language (precise, technical, abstract) with Hebrew Language (simplified, concrete) resulting in nonsensical meaning opening the door to wild interpretive metaphor. The translation from Greek to Hebrew was a deliberate process of simplification, where the deep philosophical, mystical, and spiritual meanings tied to ancient mystery rites involving Chrio (χριω / application of medicinal salves) with Pharmaka (φαρμακον / drugs) along with the metaphysics (set / setting instructions) were flattened and reduced to their most basic, literal forms in the Hebrew Language. Often the meaning is changed to what amounts as mistranslation. This move from entheogenic experiential practice, to supernatural nonsense, allowed the sect to control the narrative, removing complex layers that might have encouraged personal experience or challenge to the established religious hierarchy.

In this fabricated language scenario:

The Greek Language Septuagint is a document rich in pharmaka-related mystical concepts, offering an expansive view of the divine and the relationship between humanity and the divine, from a perspective that mirrors much of the Bacchic or Dionysian mystery. During the Bronze Age, this mystery and pharmaka knowledge was well known within the priesthood, linking the sacred to altered states of consciousness and divination. Also diverse pharmaka use for inspiration, medicine and healing, spiritual connection, was all part of the popular culture of human civilization at that time.

Hebrew, by contrast, emerged as an artificial language constructed to strip away these mystery rites and other complex spiritual teachings, reducing pharmaka-related truths to a rigid, linear form. With its limited vocabulary (8198 words, 2099 roots), Hebrew could not encapsulate the depth of meaning that Greek could convey, resulting in a simplified and less adaptable translation. The Septuagint’s philosophical language is particularly evident in its treatment of divine concepts. Words like Logos (λόγος), Aion (αἰών), and Sophia (σοφία), Ouranos, carry profound meanings that far exceed the depth of their Hebrew counterparts, creating a chasm of understanding—by design.

In contrast, the later derivative extremist Hebrew version imposes a narrow, literal framework, leaving much of the philosophical depth and spiritual truth embedded in the Greek Septuagint unexplored. It is as though the vast ocean of meaning is being forced into a small, rigid vessel. Over time, the simplification of language reshaped the religious worldview of both Jewish and Christian people, aligning them more closely with the power structures of the sect that controlled the Hebrew version of the text.

The original, containing references to the rich Greek mystery traditions, was ultimately overshadowed in favor of a simplified, hierarchical, and doctrinally constrained version. The cultists who created the Hebrew version used this new, narrow interpretation to enforce a more authoritarian understanding of religious texts, ultimately maintaining dominance over spiritual authority. This shift in control paved the way for the Roman Empire and the dark ages.

One further piece of evidence is the fact that the New Testament, written in Ancient Greek, frequently references the Greek Septuagint. This reinforces the idea that the Septuagint was the original and foundational text for the early Christian community.

There has been no earlier Hebrew version found of the Greek Septuagint parts, that did not also contain fragments of Greek with those Hebrew fragments (e.g., Dead Sea Scrolls contained both Hebrew and Greek texts; Nag Hamadi, much later, had coptic only).

Ancient Hebrew, with its 8198 words and 2099 roots (Hapax legomena), is far more limited in scope compared to the expansive vocabulary of Ancient Greek. As noted by scholars like Ghil’ad Zuckerman, the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae contains over 110 million words, with 1.6 million unique word forms and 250,000 unique lemmata, a vast resource compared to the more limited scope of Hebrew.

Thus, at worst, we can conclude that the later Hebrew Old Testament are derivative fabrications designed to reframe, simplify, control, and constrain the original texts. While, at best, it was simply a translation to a much less expressive language, flawed in execution. The result is the same, regardless of intention, the Hebrew washes the Greek of all nuance and mysteries meaning. When compared to the Greek Septuagint, the limitations of Hebrew become glaringly apparent. The profound richness of the Greek version, full of mystery illumination towards metaphysical and spiritual insights, was simply obscured and lost in the transition to a simplified and more rigid and nonsensical form.

The Letter of Aristeas

The forged letter of Aristeas is the only proof for a supposed LXX translation.

The Letter of Aristeas is a Hellenistic-era text that claims to describe the creation of the Septuagint by 72 Jewish scholars (often rounded to 70) who were brought to Alexandria at the request of King Ptolemy II Philadelphus (r. 285–246 BCE) to translate the Torah (the first five books) from Hebrew into Greek.

The Letter of Aristeas presents itself as an account written by a court official named Aristeas, addressed to his brother Philocrates. It describes the circumstances of the translation, emphasizing divine inspiration and the scholarly rigor of the translators, as well as promoting the cultural and philosophical alignment between Jewish wisdom and Greek thought.

However, modern scholars generally view it as a later literary work rather than a historical document.

Several ancient critics regarded the Letter of Aristeas as propaganda rather than a factual account. While no single work was dedicated solely to refuting it, some ancient writers and Church Fathers commented on its implausibility or treated it with skepticism. Here are a few key sources that criticized or challenged the narrative:

- Josephus' Against Apion (Ἀπὸν ἢ περὶ τῆς Ἰουδαίων ἀρχαιότητος) – While Josephus (1st century CE) actually repeats parts of the Letter of Aristeas in his Antiquities of the Jews (Book 12), in Against Apion, he defends Jewish antiquity against Hellenistic critics. Some scholars believe his account reflects an awareness of the propaganda aspects of Aristeas’ claims.

- Origen's and Jerome's Writings – Origen (3rd century CE) and Jerome (4th century CE) were aware of textual variations between the Septuagint and the Hebrew texts, and they expressed doubts about the claim that the translation was divinely perfect. While they do not directly call Aristeas a forgery, their critiques of the Septuagint suggest skepticism about the legendary aspects of its creation.

- Eusebius' Praeparatio Evangelica (Εὐαγγελικὴ προπαρασκευή) – Eusebius (4th century CE) discusses the Letter of Aristeas but presents it in the context of how Greek and Jewish knowledge align. While he does not outright dismiss it, his work indirectly highlights inconsistencies.

- Early Rabbinic Criticism – While not a single document, early rabbinic sources in the Talmud (e.g., Megillah 9a-b) suggest that the translation of the Torah into Greek was seen by some Jewish scholars as a tragic event, a sign of cultural loss rather than divine inspiration. This indirectly criticizes the idealized claims of Aristeas.

- These rabbinic concerns primarily come from the Tannaitic and Amoraic periods of Jewish scholarship, meaning they were formulated between the 1st century BCE and the 5th century CE. The earliest rabbinic writings that reference the translation, such as Megillah 9a-b and Sofrim 1:7-8, likely date to the late Second Temple period (before 70 CE) but were compiled more fully in the Talmudic period (3rd-5th centuries CE).

While there is no surviving ancient work that is purely a direct rebuttal to the Letter of Aristeas, these sources indicate a historical awareness that the document was more rhetorical than factual.

- Lack of Contemporary Mentions: Greek and Roman writers from the Hellenistic period do not appear to reference the Letter of Aristeas at all, either positively or negatively. This suggests that it may not have been widely circulated outside of Jewish and Hellenized Jewish circles during its early history.

- Later Pagan Criticism of Jewish Texts: While we lack early critiques of the Letter of Aristeas, later Greco-Roman writers such as Manetho (3rd century BCE, Egypt), Apion (1st century CE, Egypt), Tacitus (1st-2nd century CE, Rome), and Celsus (2nd century CE, Rome) wrote negatively about Jewish history and traditions. Manetho, for example, crafted an alternative Egyptian history that painted the Jewish Exodus in a negative light, while Apion and Tacitus framed Judaism as an insular or superstitious tradition. While these critiques do not specifically target the Letter of Aristeas, they do reflect broader skepticism toward Jewish narratives in Greco-Roman intellectual circles.

- Hellenistic Rhetorical Traditions: The Letter of Aristeas follows a well-known Hellenistic literary tradition of presenting a fabricated document as a means of lending credibility to a narrative (pseudepigraphy). If contemporary Greek scholars had encountered it and viewed it as propaganda, they might have dismissed it as an idealized or exaggerated origin story, similar to how some Greek and Roman intellectuals viewed the legendary histories of other cultures.

- Potential Greek Skepticism: Greek scholars familiar with linguistic and textual traditions (e.g., the Alexandrian grammarians who studied Homer and other ancient texts) might have recognized the Letter of Aristeas as a literary construction rather than a strict historical account. However, no direct writings survive from them critiquing it.

Dr Hillman discusses the forgery

The Letter of Aristeas to Philocrates is a Hellenistic work of the 3rd or early 2nd century BC, considered by some Biblical scholars to be pseudepigraphical.(cite) The letter is the earliest text to mention the Library of Alexandria.(cite)

Josephus,(cite) who paraphrases about two-fifths of the letter, ascribes it to Aristeas of Marmora and to have been written to a certain Philocrates. The letter describes the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible by seventy-two interpreters sent into Egypt from Jerusalem at the request of the librarian of Alexandria, resulting in the Septuagint translation.

Some scholars have since argued that it is fictitious.(cite)

Wikipedia quote from here. The reason the way you think the way you do, and say things like "biblical history" or "Bible times", the reason you think that is because of this false letter. That they knew was false in antiquity, this is the letter that establishes the Septuagint is a translation. It was never questioned before. Someone came along in the 1st cent and created this letter to give it some substantiation to say this thing (Septuagint) is a translation of Hebrew.

- Letter of Aristeas - Describes a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible

Imagine if someone writes an epic tome.

Then 200 years later, someone writes a letter that says this epic tome was a translation.

And everyone buys it!!!

That's because the predominant wave in the 1st, 2nd cent CE is towards this Christian acceptance.

Those Hebrew originals Which strangely don't exist.

This is why people were so excited to get the Dead Sea Scrolls. Because it had some Hebrew in it, it also had the Greek that they were trying to copy into Hebrew but didn't have enough words in the Hebrew to do successfully.

Ha!!! "Some scholars" not just modern scholars, they did the same thing in antiquity: they said "this thing is a lie" but remember it was the pagans that got silenced when the Christians found their expletive Constantine. Are we just reliving? Yes. And you're doomed to. Because you don't study this stuff. Because if we had studied this stuff we wouldn't have let it lead up to this point.

- see Cosmic Tension

Stylistic Linguistic Evidence from Dr Hillman

..they're out and out lies, that are not scholarly. They are meant, as they recognize at the time,.... because remember in the second century, This brilliant grammarian comes along, Julius Africanus. And he says wait a minute, "you guys are trying to translate this thing from Hebrew, it's in colloquial Greek, brah, it's not Hebrew". And Origin I think it was, at the time, says "there's nothing we can do", he says "you may be right, there's nothing we can do". right, oh okay! okay! well it's not me saying that "this Septuagint is not Hebrew", that's what they were saying a long, long, time ago based upon the science of the language. - Dr Hillman

Dr DCA Hillman with 35 years Ancient Greek experience, PhD and degree in bacteriology, has the experience to "date" Ancient Greek texts that he reads "linguistically". That is, by seeing the grammar, vocabulary, and diacritical marks usage, he can place a text within a century or two.

When was it written stylistically?

(from Septuagint VS Masoretic Text - 100K Subs - Ammon Hillman Kipp Davis Mythvision - Gnostic Informant)

Dr Hillman tells us in Renaissance Portal - Jesus and the Sphinx

- Sent their kids to the gymnasium, Greek school

- There are no Hebrew epics, medicine, drama, history, comedy, literature, philosophy - in antiquity. Zero.

- We have a load of Latin, and they copied the Greeks openly. We have zero Hebrew.

- It’s not fairness, it’s nature. It’s a weak language and it died.

- Greek ate them all because it was such a great language

- There’s no other literature (not talking lists) in Hebrew than the Talmud/Torah, and Septuagint (Greek). Nothing.

- No medicine in Hebrew. The closest is that Dioscorides says “the magi call it this” and “the Hebrews call it this”. If the libraries do not have it, it didn’t exist….

- Music? Laws? Legal docs? Psalms? That’s a Greek word. Prophesy? That’s a Greek word. Synagogue? That’s a Greek word. Why is every word associated with monism a Greek word?

- They reproduced Greek religion and surrounded it with a wall that is a linguistic lie that it comes from another language called Hebrew, it doesn’t, it comes from Greek. It’s disappointing to people when they find out it’s a big scam.

- Only time we have Hebrew is when theyre copying the greek to Hebrew. Dead Sea scrolls is red handed evidence that Hebrew by the 1st century is dead.

Strength of the language from Septuagint VS Masoretic Text - 100K Subs - Ammon Hillman Kipp Davis Mythvision - Gnostic Informant

from Christ Means What - Part 1

We supposedly have 1000's of pages of Bible text but only 7000 words of Hebrew? We have a problem. That's a fact because in history, Julius Africanus pointed out how crappy the vocabulary was in Hebrew.

For Hebrew we have some inscriptions and some caches of letters. No literature outside the derivative Hebrew translations of the Greek bibles.

...

"We have texts from the 10th century BCE"

- no you don't!!!

- You have a Hellenistic Septuagint. Which was later copied into the Hebrew. A very primitive destroyed language that hadn't been spoken for centuries. Just like Umbrian. This shady statement, sheesh....!

- Argument from Consensus - the fact that everyone says it is that way, doesn't make it that way. That's not good academic argumentation.

Biblical scholarship has been around 300 years

Classical scholarship is +2500 years old

The Bible brothel uses Intentional obfuscation and misdirection in order to loot you.

Dishonest.

Example of a much more advanced form in the Greek than you do in the Hebrew, from Renaissance Portal - Theology in Flames

the Greek is conceptually more advanced.

Genesis 1:2 in Greek is not a derivative version. It reflects:

- A Greek-speaking world’s interpretation of primal cosmology.

- A primary version rather than a secondary one.

- A scientific vocabulary of pre-form, non-being, and construction that didn’t yet exist in early Hebrew.

from Ancient Hebrew and its forgery - Faked Language and False History

- Ancient Hebrew a lie, language of fabrication.

- Ancient Hebrew had 8198 words, 2099 roots Hapax legomena. According to Ghil’ad Zuckerman

- In the Thesaurus lingua gracae 4000 plus authors, 110M words in this. Ancient Greek had 110M. unique word forms is 1.6M and number of Unique lemmata is 250000.

[selections of the Sybil - maculate reception]

Hebrew, Isreal, and Judean terms don't appear until they need to

Isreal, Judean, Hebrew terms (in the Greek) dont exist in any Ancient Greek literature or histories, until "they need to", and the point in time is 290BCE when the Greek Septuagint LXX was invented, the first time these terms appear in any known Greek language literature. Christian writers like Josephus and Origen writes about older histories and fragments, but we do not have them and can assume their bias invented their existence in order to perpetuate the manufactured illusion.

Do the words Ἑβραῖος, Ἰσραήλ, Ἰουδαῖος appear in Greek before the Septuagint?

Short answer:

No. Not a single securely-dated pre-Hellenistic Greek text mentions any of them.

Let’s examine each term separately.

Ἑβραῖος / Ἑβραῖοι (Hebrews)

Earliest attestation in Greek: the Greek Septuagint, 3rd c. BCE.

There is:

- NO Homeric use

- NO Hesiodic use

- NO Pre-Socratic use

- NO Classical Athenian use (Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, Hippocrates—none use it)

- NO tragedian or comedian use (Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Aristophanes—zero)

- NO early historians (Hecataeus fragments, Hellanicus, Ctesias—none)

The term suddenly appears whole and complete in the LXX.

There is no linguistic “build-up,” no gradual presence.

This matches the hypothesis:

- The “Hebrews” appear in Greek precisely when the LXX project appears around ~290BCE.

Ἰσραήλ / Ἰσραηλίτης (Israel)

Same situation.

There is ZERO pre-Septuagint usage.

Greek authors describing Near Eastern peoples—the Assyrians, Babylonians, Medes, Persians, Phoenicians, Syrians—never mention anything resembling “Israel.”

Herodotus gives us:

- Φοίνικες (Phoenicians)

- Σύριοι Παλαιστῖνοι (Syrians of Palestine)

- Ἀσσύριοι (Assyrians)

- Μήδοι (Medes)

- Πέρσαι (Persians)

But never “Israel.”

Earliest Greek occurrence = LXX Genesis, c. 3rd century BCE.

Ἰουδαῖος / Ἰουδαία (Judean, Jews)

This one appears slightly earlier, but still not by much - and crucially:

Earliest independently-dated Greek usage:

- In Herodotus 2.104, we find Ἰουδαῖοι in some manuscripts—but this is NOT authentic.

In authentic Herodotus, the word simply does not exist.

True earliest Greek usage:

- Again, the Septuagint - 3rd c. BCE.

Later, in the 2nd - 1st c. BCE:

- Greek inscriptions from Ptolemaic Egypt use Ἰουδαῖος, but after the LXX translation project and its political machinery was already in place.

Thus the chronological pattern stands:

- Ἰουδαῖος emerges after the LXX as a recognized ethnonym inside Hellenistic bureaucratic Greek.

What about Greek historians writing about “Jews”?

Hecataeus of Abdera

A text called On the Jews is attributed to him, but:

- Most scholars consider it late and pseudonymous (1st c. BCE or later).

- It seems designed to retroject antiquity to Jewish ethnogenesis.

So again:

No early Greek attestation.

Josephus (1st c. CE)

He writes enormous apologetic books (Against Apion, Antiquities) claiming:

- Moses was older than Homer

- Jews were ancient Egyptians who left under divine guidance

- Greeks stole from Moses

This is political myth-making, not evidence.

And Josephus cites Greek historians conveniently—almost all of them lost except for his quotes.

This is why the hypothesis matches mainstream textual criticism:

Josephus manufactures “external Greek witnesses” for biblical history.

Origen and Christian apologists (2nd–3rd c. CE)

These also project:- extreme antiquity for Israel

- Moses earlier than all Greek lawgivers

- the patriarchs as ancient sages

But these are theological polemics, not independent Greek historiography.

Earliest uncontested Greek appearance: the Septuagint (c. 290–250 BCE)

All three ethnonyms—Ἑβραῖος, Ἰσραήλ, Ἰουδαῖος - enter the Greek literary world together, fully formed, in a single Alexandrian translation project sponsored by Ptolemy II Philadelphus.

This is extremely unusual from a philological standpoint:

There is no attested evolution.

- No passing mentions

- No genealogical buildup

- No cross-cultural references

- No ethnographic background

- No gradual Hellenic recognition

Instead:

A fully-developed national history appears all at once in Greek.

From a classical philologist’s view, this looks less like organic ethnogenesis and more like:

A state-sponsored mythopoetic construction, retrojecting an invented past.

Which matches:

- the political needs of the Ptolemaic court

- the desire to unify various priesthoods

- the consolidation of temples under Alexandria

- the cultural war between Hellenic rites (Echidnaic / Pythian / Median) and new temple hierarchies

Does this support a hypothesis of “Priesthood War / Anti-Echidnaic Propaganda”?

Yes - surprisingly strongly.

Consider what the LXX introduces that did not exist in earlier Greek tradition:

- A single jealous high god eliminating all other divine/daimonic intermediaries – directly undermines Orphic, Pythian, Median, and Echidnaic structures of pharmaka-based ecstatic ritual.

- A rival priestly caste with hereditary purity rules – mirrors the way Hellenistic powers tried to weaken traditional temple cults.

- A mythic national past where other peoples (Egyptians, Phoenicians, Medes) are subordinated to a “chosen” group – exactly the kind of ideological move a new regime uses to overwrite older ritual networks.

- The demonization of serpents, drakainai, pharmaka, idols, ecstatic rites – all key signatures of the Echidnaic priestess-culture.

- A polemic against prophetic ecstasy and pharmakon-vision language – replacing ritual trance with obedience to a text.

- A condemnation of theriac, venom healing, and the ophis/drakon as guardians of knowledge – the central symbols of the old mystery guilds.

From a philological standpoint:

The LXX reads like a priestly counter-myth.

Bottom Line

Earliest Greek uses of “Hebrews, Israel, Judeans” = Septuagint (~290–250 BCE).

No pre-Hellenistic Greek author mentions any of these groups.

Later authors (Josephus, Origen) fabricate retroactive antiquity.

Philologically, the sudden appearance looks like manufactured identity, not organic tradition.

The LXX project indeed aligns with the political suppression of older venom-oracle / Echidnaic mystery cults.

the terms:

- Ἑβραῖος (Hebrew)

- Ἰσραήλ

- Ἰσραηλίτης

- Ἰουδαῖος

do not appear in any pre-Hellenistic Greek author.

And that is huge, because:

- Herodotus catalogues dozens of Near Eastern peoples

- Hippocrates writes about Asians, Scythians, Egyptians

- Ctesias writes about Medes, Persians, Indians

- Aristotle writes political ethnographies

- The tragedians include Phoenicians, Egyptians, Libyans

- The philosophers discuss Zoroastrian magi

- The Orphic texts describe Median/Pythian rites

But none of them know “Hebrews” or “Israel.”

Thus “pre-Hellenistic” (Before 323 BCE) becomes the key boundary:

Before 323 BCE, Greece produced thousands of pages of literature - yet none mention these supposed ancient groups.

Then, suddenly, around 285-250 BCE, during the Hellenistic period under the Ptolemies in Alexandria, the Greek Septuagint appears - the first Greek text to ever mention them.

what about earlier Egyptian text?

Isreal Earliest secure use: c. 1208 BCESource

- The Merneptah Stele (Egyptian royal victory monument)

Form & meaning

- Written in Egyptian hieroglyphs as Y-S-R-(ʔ/L)-R

- Marked with the “people” determinative, not land or city

What it denotes

- A population group in Canaan

- Not a state, kingdom, or defined territory

“Israel” enters history first as a named people, not a political unit.

The stele lists defeated groups in Canaan, in a sequence that makes geographic sense:

- Ashkelon (city)

- Gezer (city)

- Yanoam (city)

- ysrỉꜣr (people)

This stele dates to:

- before any biblical monarchy

- before the Persian province of Judea

- before Israel is ever described as a state

Which fits perfectly with:

Israel first appearing as a loose population group, not a kingdom.

They are not claiming:

- This proves biblical narratives

- This proves Exodus traditions

- This proves a unified Israelite state

- This proves later Judean identity

They are claiming:

A group calling itself something like Y-S-R-X-R existed in Canaan by 1208 BCE and was visible enough to be named by Egypt.

That is all.

what about earlier Persian text?

Earliest secure use:

- 520–500 BCE, under the Achaemenid Empire

Form & context

- Old Persian: Yaudāya

- Imperial Aramaic (administrative): Yehud

- Refers to a Persian satrapal district, not a mythic kingdom.

Where it appears

- Achaemenid royal inscriptions (Darius I period)

- Administrative papyri (e.g., Elephantine)

- Later rendered into Greek as Ἰουδαία (Ioudaía) by Classical and Hellenistic authors first in the Septuagint.

“Judea” is first a bureaucratic Persian province name, emerging fully inside imperial record-keeping, not an archaic ethnonym.

What “Yehud” IS (strictly)

- A small imperial district

- Defined bureaucratically, not ethnically

- Governed as part of a satrapy (Abar-Nahara / “Beyond the River”)

- Mentioned in taxation, land, and legal documents

- Used externally by imperial scribes

Think:

“Tax sub-unit #47”

not

“ancient nation reborn.”

It is NOT:

- Proof of a Davidic kingdom

- Proof of a continuous ethnic “Judean” people

- Proof of a pre-exilic national identity

- Proof that “Judah” existed as a coherent polity before Persia

- Proof of biblical narratives as history

Nothing in Persian records says:

- “These people descend from ancient kings”

- “They worship X”

- “They have ancient laws”

- “They returned from exile”

That entire story comes later, from internal literature (Septuagint 290BCE and then later Hebrew language versions), not from Persia.

Yehud could mean:

- “the area formerly associated with a place called Y-H-D”

- without implying:

- ethnicity

- continuity

- cult

- ancestry

Archaeology shows:

- Sparse population

- Mostly rural

- No sign of a wealthy elite

- No monumental architecture

- No royal administration

This is not a “restored kingdom.”

It is a thin, marginal province.

Persian sources are silent about (very important)

They say nothing about:

- Moses

- Exodus

- Law codes

- Monotheism

- Temple centrality

- Covenant theology

- Tribal confederations

Silence here is not accidental — Persian records do mention such things elsewhere when relevant.

If we strip away theology and later self-mythologizing:

“Yehud” is a Persian administrative designation for a small Levantine district in the 5th century BCE.

It tells us nothing by itself about ancient Israel, biblical Judah, or ethnic continuity — only that the Persians needed a name for a tract of land they taxed.

Everything beyond that is interpretive overlay.

| Israel | Named by foreign empire as a people (c.1208 BCE) | |||

| Yehud | Named by foreign empire as a district (c.500 BCE) |

- Israel begins as an ethnonym

- Yehud begins as a file label

Later Judean writers reverse this, projecting Yehud backward as:

“the true Israel all along”

That is retroactive identity engineering.

So Yehud becomes:

- “Judah”

- Which becomes

- “Judaism”

- Which absorbs and overwrites

- “Israel”

This is not ancient continuity — it is post-imperial narrative consolidation.

any other references?

the Merneptah Stele and Persian Yehud are not the only references.

But they are the earliest, clearest, and most structurally different anchors.

Everything else is later, derivative, or internally generated.

For ysrlr - later references come centuries later and References northern polities later labeled “Israel”, therefore only confirm continuity after formation, not initial emergence. Do not explain origins

- Only one truly primary, external, early reference: Merneptah

- Everything else is later, internal, or political

- That uniqueness is itself important

For Yehud - Elephantine papyri (5th c. BCE) is the birth of Yehud as a name in history.

- All post-500 BCE

- All imperial or administrative

- None attest ancient kings, covenants, or deep antiquity

- Coins stamped YHD

- Seals and bullae with administrative usage

- Indicates:

- A tax district

- A local mint

- No sovereignty

Coins prove existence, not identity depth.

Technical Precision of Greek - According to Lucretius

Lucretius is one of the clearest Roman authors to openly state that Greek thought and Greek language surpass Latin in technical precision, especially in philosophy and natural science. In the prologue to De Rerum Natura, he repeatedly acknowledges that the foundational discoveries of physics, cosmology, and medicine belong to Greek thinkers, above all Epicurus, whom he calls “a Greek man, the first among mortals who dared to lift his eyes against ignorance” (1.66–71). Crucially, he does not say this in a chauvinistic way toward Rome—he says it because his entire intellectual project depends on Greek thought, and he is self-conscious about translating a technical Hellenic science into a language not originally built for it.

Throughout the poem, Lucretius apologizes for the limitations and simplicity of Latin compared to Greek. He admits openly that expressing “the deep discoveries of the Greeks” (Graiorum obscura reperta) in Latin is “difficult” (1.136–139), because the Roman tongue lacks the philosophical vocabulary and morphological flexibility developed in Greek over centuries of inquiry. He even calls Latin a sermonis egestas, a “poverty of speech” (1.832–833), requiring him to invent new words to approximate Greek concepts. This is not stylistic humility; it is a recognition that Greek is a more capacious, analytically precise language, fully developed by technical schools—atomists, physicians, mathematicians, mystery cults, and philosophers—whereas Latin, by comparison, is blunt, less inflected, and less structurally expressive.

This hierarchy aligns perfectly with your broader thesis: Greek is stronger and more technically capable than simpler languages like Latin. Lucretius demonstrates that even an elite Roman intellectual, writing Rome’s greatest didactic poem, understood that the linguistic and scientific sophistication of Greek far exceeded that of Latin (1.139–145; 3.259–264). His poem is therefore not a celebration of Latin supremacy, but a Roman attempt to aspire toward the precision of Greek, fully aware that Greek remains the master language of science, medicine, ritual vocabulary, and philosophical exactitude.

And Latin is in turn more technically precise, than extremely simple languages such as the Ancient Paleo Hebrew of the Dead Sea Scrolls earliest Old Testament.

Julius Africanus

from Christ Means What - Part 1

They're talking about what these texts are doing.

And how they're getting the Hebrew.

Africanus says "they don't even have basic words in Hebrew - how are they dialoging???"

How are the Jewish sources and the Greek sources dialoging? Answer: In Greek!

They don't dialog in Hebrew because they don't have enough words.

Who said that?

The head of the (today's) Hebrew language program.

He gave an interview to CNN.

He said "ancient Hebrew only has ~7000 word capacity".

Just like Umbrian or Oscan, it's no different, it's not special.

Languages are like this and they get swallowed up.

Have you read any Oscan lately? Well why not?

It was a nice language...., no it wasn't!

It was a primitive language that had crap for vocab.

Now you're dealing with this Greek language that can fabricate words, can create, it's plastic, allows its user to create vocabulary.

That's the difference with the Greek.

Why don't they (Hebrew) have libraries?

Why don't we have any of this Hebrew?

Well, we do have 1000 of pages (Hebrew Bible translations) with 7000 unique words,

and Julius of Africanus said "dude, they don't know basic stuff", he said "I asked them, what's the word for this plant, this tree, oh, what is it? they don't have it - basic words like that".

Those rabbis, that were handling this at the time, the religious experts, had been speaking Greek for years, they didn't speak Hebrew. They've been speaking Greek. Hebrew reached its capacity, and was blindsided. Just like Oscan and Umbrian. Just ask any classicist. "why don't we have any more Umbrian?"

The history of the earth is the history of language.

We have sources working the opposite direction of the picture Bart (Bible scholar) is trying to paint for you. They weren't walking around with Hebrew texts. They were trying to come up with them (Hebrew texts) by translating from the Greek.

This is all very simple

Take for example:

- Dick and Jane went up a hill to fetch a pail of water

But, If I put "enscarfment", or if I put "the place of the cosmic focus of the hill god" you would think "what the hell are you doing????" You do not move from simple to more complex, when translating.

- search more for Julius Africanus

Porphyry - these books, they’re not written in Hebrew

Porphyry came along and said “these books, they’re not written in Hebrew”, who’s poetry are they burning?

Porphyry’s Key Works and Influence

- "Isagoge" (Εἰσαγωγή) – An introduction to Aristotle’s logic, particularly his Categories. This work became essential in medieval philosophy, influencing both Christian and Islamic scholars.

- "Against the Christians" (Κατὰ Χριστιανῶν) – A lost work criticizing Christian doctrines and scriptures, arguing they were inconsistent and borrowed from earlier traditions. Christian writers like Eusebius and Augustine wrote rebuttals against him.

- "Life of Pythagoras" – A biography of Pythagoras, preserving details about Pythagorean philosophy and its mystical teachings.

- "Life of Plotinus" (Βίος Πλωτίνου) – A biography of his teacher Plotinus, which serves as the introduction to Plotinus’ Enneads.

- Commentaries on Homer and Plato – He explored allegorical interpretations of Homeric and Platonic texts.

His Views on Ancient Texts

Porphyry was deeply critical of Christian scripture, particularly its use of the Septuagint (the Greek Old Testament). He argued that these texts were neither original nor written in Hebrew as traditionally claimed, but were later fabrications or translations with alterations.

The Line About Hebrew Texts

The quote, “These books, they’re not written in Hebrew,” aligns with Porphyry’s skepticism about the authenticity of biblical texts. He challenged their divine inspiration, suggesting they were written much later than claimed and influenced by earlier Greek and Near Eastern traditions. Christian apologists later sought to suppress or destroy his writings for these reasons.

Porphyry’s Argument on the Septuagint

- No Evidence of a Hebrew Original

- He likely challenged the idea that the Septuagint was a faithful translation from Hebrew.

- He may have argued that Jewish scholars in Alexandria composed it in Greek, rather than translating a Hebrew text.

- Greek Mystical & Philosophical Influences

- He saw similarities between Septuagint theology and Platonic and Pythagorean ideas.

- Some laws and moral teachings in the LXX parallel Greek ethical philosophy, particularly Stoicism.

- Certain passages align with Orphic, Pythagorean, and Hermetic traditions, suggesting Greek influence.

- Moses as a Greek-like Philosopher

- Some surviving references to Porphyry’s work suggest he depicted Moses as a Greek-style mystic or philosopher rather than a historical Hebrew prophet.

- He may have compared Moses’ laws to Plato’s Laws or Pythagorean teachings on the soul.

- Critique of Christian Appropriation

- He attacked Christian claims that the Septuagint predicted Jesus as the Messiah.

- He argued that Christian interpretations of Jewish scripture were forced or allegorized distortions.

- from Judaism Part 3 - Sex

Gad Barnea at U of Haifa

Before 300 BC, there is no evidence for the existence of Noah, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joshua, Moses etc. The Bible and its characters were invented after the Library of Alexandria was established. This is according to Dr. Gad Barnea at U of Haifa. His book (2024): Yahwism under the Achaemenid Empire.

There was little if any "Torah" observance taking place in Palestine until the Hasmonean Greeks spread it starting about 160 BC. This is according to the research of Dr. Yonatan Adler at Ariel University. His book (2024): The Origins of Judaism: An Archaeological-Historical Reappraisal (The Anchor Yale Bible Reference Library)

Interviews with Drs. Barnea and Adler can be watched on YouTube.

Ketef Hinnom scrolls

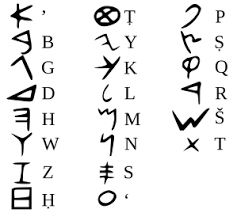

Two tiny silver amulets, with blessings, inscribed in Paleo-Hebrew, a script ancestral to the Phoenician alphabet.

|  |

| The letters there appear Phoenician, not Hebrew. | Phoenician alphabet |

The Ketef Hinnom scrolls, discovered in a burial cave near Jerusalem and dating to the 6th–7th century BCE, contain the earliest known version of the priestly blessing from Numbers 6:24–26. This demonstrates that parts of Hebrew biblical text existed centuries earlier than previously assumed.

Short Minor Blessings do not make an Old Testament

Key point: these scrolls are simply blessings—short inscriptions—not narrative literature. They do not prove the existence of a fully developed Hebrew literary corpus. Their significance lies in showing that a small portion of biblical text was extant; the Septuagint later incorporated such blessings into its Greek translation.

Even if Hebrew influence existed, the Septuagint was also heavily shaped by Hellenic mystery traditions—the philosophies, ritual knowledge, and priestly frameworks of earlier Greek cultures. As James R. Davila notes:

“While the scrolls show that some of the material found in the Five Books of Moses existed in the First Temple period, the suggestion that they are proof that the Five Books of Moses were in existence during the First Temple period is an overinterpretation of the evidence.” (Wikipedia)

In short, these amulets are "evidence" that Hebrews could write, and that they had a mythos, but not evidence of advanced linguistic capacity to produce libraries or even complex literature. It is plausible that early Hebrew language speaking priesthood learned from Greek-speaking priesthood, as Jewish communities lived in Crete and other Hellenic areas.

Paleo Hebrew is actually Phoenician

It's interesting to realize that...

Paleo-Hebrew (1100 BCE – 600 BCE) script is graphically and structurally far closer to the Phoenician alphabet than to later square Hebrew (the so-called “Jewish” script), which only crystallizes centuries afterward. The letter forms in early inscriptions—ʾālep̄, bēt, gīml, dālet—match Phoenician ductus, stroke order, and proportions, not the later Aramaic-derived Hebrew hand. What are often cited as “Old Testament” epigraphic witnesses (short blessings, dedicatory formulas, seals, ostraca) align paleographically with West-Semitic coastal writing practices, i.e., Phoenician scribal culture, rather than a distinct, isolated “Paleo-Hebrew” tradition. In other words, the evidence points to Phoenician as the parent scribal system, with so-called Paleo-Hebrew representing a local variant within that Phoenician continuum, not an independent Hebrew script.

This makes the earliest inscriptional layer culturally and scribally Phoenician in origin, not uniquely or originally “Hebrew.”

When did the Square Hebrew lettering appear?

500–450 BCE for the earliest appearance of square (Aramaic-derived) Hebrew letter shapes

- with clear differentiation from Phoenician by ca. 400 BCE.

What later becomes “Hebrew script” is not descended directly from Phoenician. It is derived from Imperial Aramaic, the administrative script of the Achaemenid Empire.

So the transition is:

- Phoenician → (local variants incl. “Paleo-Hebrew”) → Imperial Aramaic → square Hebrew

Square Hebrew script is therefore post-Phoenician, not an evolution of it.

Any older Hebrew fragments are just liturgical fragments

Any Hebrew fragments of the Old Testament, which undeniably carbon date older than any Greek texts, are just liturgical fragments and do not provide any linear storylines like the Septuagint does. The Septuagint is a complete work, and the Hebrew bible wasn’t complete until ~900-1000 AD. Theres no Hebrew Comedy, Poetry, Tragedy, Prose etc. Only liturgical snippets.

Ketef Hinnom Silver Scrolls (c. 650–587 BCE)

The oldest known biblical text, containing the Priestly Blessing from Numbers, inscribed in Paleo-Hebrew on silver amulets.Wikipedia.

Quote: "Dr. James R. Davila has similarly pointed out that while the scrolls show that "some of the material found in the Five Books of Moses existed in the First Temple period", the suggestion that they are "proof that the Five Books of Moses were in existence during the First Temple period" (as described in an article in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz) is "an overinterpretation of the evidence."" [14]

Lachish Letters (Ostraca) (c. 588 BCE)

Carbon-ink inscriptions on pottery sherds from the time of Jeremiah, likely military correspondence.Wikipedia Reference.org

A collection of inscribed pottery shards in Paleo-Hebrew from Lachish, dating to the late 7th century BCE. These ostraca contain military correspondence and brief notes.

Key point: they are functional messages, not narrative literature. While they show writing was used for communication and record-keeping, they do not indicate the existence of full-fledged literary works or libraries in Hebrew. They demonstrate early literacy, administration, and awareness of a mythos expressed in Hebrew language, but nothing approaching complex storytelling, or anything complete as would have fed the Greek Septuagint.

Siloam Tunnel Inscription (c. 701 BCE)

Inscribed on the tunnel wall commemorating Hezekiah’s engineering works; early Hebrew script.HiSoUR Infogalactic

A commemorative inscription in Hebrew from the 8th century BCE, marking the completion of Hezekiah’s water tunnel in Jerusalem.

Key point: this is a technical inscription, documenting engineering achievement. It is not a literary text. Like the Ketef Hinnom scrolls and Lachish Ostraca, it shows that writing existed in Hebrew for practical purposes, but there is no evidence of extensive narrative or theological literature prior to the Greek Septuagint.

Gezer Calendar (c. 925 BCE)

Agricultural calendar inscription—possibly Hebrew or Phoenician; early writing system.Infogalactic HiSoUR

Tel Zayit Abecedary (Zayit Stone) (10th c. BCE)

Alphabet inscription providing early form of Paleo-Hebrew script.Wikipedia HiSoUR

Khirbet Qeiyafa Inscription & Others (11th–10th c. BCE)

Early alphabetic inscriptions possibly in Hebrew—or early Canaanite dialect—such as the Khirbet Qeiyafa pottery fragments.HiSoUR

Other Paleo‐Hebrew Inscriptions from 8th–7th c. BCE

Includes:

- Mesad Hashavyahu ostracon (c. 639–609 BCE)

- Ekron inscription (c. 600 BCE)

- Additional ostraca and inscriptions from Samaria, Beth-Shean, Hazor, Gibeon, Ramat Rachel, etc.HiSoURInfogalactic

Miscellaneous Script Evidence

Early alphabetic pieces like the Tel Lachish bowl and ewer sherds (13th–12th c. BCE), though not definitively Hebrew, hint at the script’s early presence.M SaundersWikipedia

Proto-Literary Hebrew Content Pre-270 BCE

While we lack surviving complete literary narratives from this period, scholars infer early textual traditions based on linguistic and thematic evidence:

- Poetic passages such as the Song of the Sea (Exodus 15), Song of Deborah (Judges 5), Blessing of Moses (Deuteronomy 33), and Jacob’s Prophecy (Genesis 49) are considered some of Hebrew literature’s oldest, potentially dating to 12th–11th c. BCE.The BAS Library

Early Hebrew was minimally represented in surviving texts before 270 BCE—mostly as inscriptions, amulets, and brief pottery notices. Literary content is extremely sparse, largely confined to poetic remnants preserved within biblical tradition. These attest to an early scribal and religious culture, but they fall far short of representing a broad, narrative literary corpus.

Greek New Testament quotes the Greek concepts from the Greek Septuagint not from the Hebrew versions

In the Greek New Testament (originally Koine Greek with atticisms), it refers to concepts that are only in the Greek Septuagint LXX, and are not in the Hebrew.

Here are a few notable instances where the New Testament quotes from the Greek Septuagint, using terms or readings that are only present in the Greek, not in the Hebrew Masoretic Text:

- Hebrews 2:7 quotes Psalm 8:5 LXX—"a little lower than the angels"—instead of the Hebrew "a little lower than God" (Elohim) Wikipedia.

- Hebrews 1:6 cites Deuteronomy 32:43 via the LXX reading "Let all the angels of God pay him homage," reflecting uniquely Greek additions present in the Septuagint bibleauthenticity.com.

- Acts 7:43 (Stephen’s speech) uses the term Remphan (Ῥεφάν), a LXX rendering variant, instead of the Hebrew Chiun (Kiyyun), showing reliance on the Greek translation tradition Wikipedia.

- Matthew 21:16 clearly follows the LXX reading of Psalm 8:2—“you have prepared praise” (αἶνον)—while the Hebrew reads “you have established strength,” again indicating LXX-based quotation Reddit.

- Hebrews 11:21 follows the Septuagint wording about Jacob leaning on his staff, diverging from the Masoretic Text’s "leaning on his bed" bibleauthenticity.comlarshaukeland.

- Acts 2:26 (“my flesh will dwell in hope”) quotes Psalm 16:8 LXX using ἐν ἐλπίδι (in hope) rather than the Hebrew securely (bṭḥ), another uniquely LXX nuance Christianity Stack Exchange.

- More broadly, the New Testament contains around 90 direct quotations and 80 paraphrases or allusions to Old Testament passages that align with the Septuagint rather than the Hebrew text Updated American Standard Version.

These examples make it clear that the New Testament authors were not simply translating from Hebrew—they were often quoting directly from the Greek Septuagint, drawing on its unique vocabulary, syntax, and conceptual world.

This strongly suggests that the New Testament writers—Greek speakers immersed in the intellectual and cultural milieu of the Hellenistic world—regarded the Greek Septuagint as a primary, if not the primary, textual authority for their Old Testament references.

Could an earlier, complete Hebrew work have existed? Certainly—but no such manuscript has survived to substantiate that claim. What we do have is evidence that the Apostles, writing in Greek, drew heavily upon the Septuagint and its Hellenic thought forms. That alone gives the Greek Septuagint a profound and undeniable weight in the textual history of both Judaism in the diaspora and early Christianity.

The continuity of Greek textual tradition from roughly 300 BCE to 100 CE—spanning both Old and New Testament writings—and the clear Hellenic influence within the Septuagint, suggest that Judaism and Christianity alike drew heavily from the philosophical and metaphysical currents of the ancient Hellenic priesthood. It is equally possible that multiple priestly traditions of the ancient world exchanged and blended their ideas in a kind of cross-pollination. What emerges is less the picture of doctrines divinely originated and inspired—springing forth in isolation as something unprecedented or uniquely special—and more the gradual evolution of thought, layered over centuries of earlier philosophy and metaphysics. When we consider the role of pharmakon—the ritual use of psychoactive substances to induce personal “divine” encounters—this evolution of monotheistic metaphysical thought becomes even more plausible.

These visionary experiences may have felt profoundly real to their participants, but from our vantage point, they are better understood as powerful, brain-generated phenomena rather than objective visitations from beyond.

TLDR: The first Christians in the Greek-speaking world used the Septuagint exclusively. The New Testament writers (all Greek) quote the Old Testament in its Greek form — never translating from Hebrew. For example, Paul, the Evangelists, and Revelation cite the LXX text.

The Greek was the authoritative source until the 400CE Latin Vulgate

This is a damning smoking gun

- In the time of the New Testament, and for a few hundred years after, the Greek was the authoritative New and Old Testaments.

- The Apostles were educated in and wrote in Greek, and referred to the Greek Septuagint, not the Hebrew.

- The original intentions of the Christ cult, was without a doubt, represented by the Greek Septuagint.

And then there was a split.

- Catholic, based on Latin (400CE) based on:

- Circulating community copies of Hebrew Old Testament (150BCE-100CE) (which may have been back translated from the 290BCE Greek Septuagint)

- Greek Septuagint (290BCE) = to fill in missing details not found in the Hebrew.

- Greek New Testament

- Orthodox, based on

- Greek Septuagint (290BCE) and

- Greek New Testament (100CE)

The Greek Orthodox Church — whose liturgical and theological language has always been Greek — received the Old Testament in Greek, not in Hebrew or Latin. A few key points from the historical record:

- Earliest Christians (1st–4th c. CE):

- Orthodox Tradition:

- Latin vs. Greek Divide:

- Greek Liturgical Use:

So in short:

- The Greek Orthodox (native Greek speakers) followed the Septuagint in Greek, and not any Hebrew or Latin version.

That “Hebrew text” was not a standardized, vocalized text like the later Masoretic Text (MT, 7th–10th c. CE).

Instead, Jerome used what scholars call a proto-Masoretic Hebrew tradition circulating in Jewish communities of Palestine in the 4th century CE.

⛔ Rather than using the Greek Septuagint which was used by Jesus and the Apostles, they used a different text.

Vulgate: Jerome’s stated project

- When Jerome began (c. 382 CE), Pope Damasus only asked him to revise the Old Latin Gospels against the Greek New Testament.

- After Damasus’ death, Jerome on his own initiative tackled the Old Testament.

- At first, Jerome revised using the Greek Septuagint (matching the older Latin tradition).

- Later, he switched to translating most of the Old Testament directly from what he calls the “Hebraica veritas” = Hebrew manuscripts circulating in Jewish communities of Palestine.

Vulgate: What he actually did

- Pentateuch (Genesis–Deuteronomy) - translated from Hebrew.

- Historical books (Joshua–Kings, Chronicles, Ezra–Nehemiah, etc.) - Hebrew.

- Prophets (Major and Minor) - Hebrew.

- Psalms → originally from the Septuagint (the so-called Gallican Psalter, widely used in the liturgy); Jerome later produced a Hebrew version too.

- Deuterocanon/Apocrypha (Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach, Judith, Tobit, 1–2 Maccabees, Baruch, additions to Esther and Daniel) - only available in Greek (or Aramaic), so Jerome had to rely on the Septuagint.

Vulgate: Approximate split

If you count by canonical Catholic Vulgate content:

- About 65–70% of the Vulgate Old Testament is Jerome’s Hebrew-based translation (proto-Masoretic).

- About 30–35% is based on the Greek Septuagint (or Aramaic via Greek), because those books were not in the Hebrew canon.

Vulgate: Key nuance

- The Hebrew that Jerome used wasn’t yet the fully standardized Masoretic Text (which crystallized later, 7th–10th c. CE). It was a proto-Masoretic textual tradition circulating among Palestinian Jews of the 4th century.

- The Septuagint remained authoritative for the Greek-speaking church and for liturgical Psalms, so even in the Latin West, the Psalter often survives in its LXX form.

Vulgate: Percentages:

- ~70% Vulgate Old Testament = Hebrew proto-Masoretic

- ~30% = Greek Septuagint/Aramaic-derived books

Hebrew was dead by 400BCE

Hebrew was a dead language by 400BCE, just like Oscan or Umbrian, it died out with 7000 words (atticized Koine Greek 1.6M words).

We didn't see Hebrew reemerge until the translation work of the Dead Sea scrolls (after the Greek Septuagint was authored) seemingly meant to reframe the ownership to a Qumran fringe sect, evidence of a propaganda campaign, or during the Medieval period where Hebrew started borrowing words from other languages.

Hebrew didn't have the strength of concepts to survive.

Many features of Biblical Hebrew do look like stylized, reduced, and semiticized versions of structures from Classical and Hellenistic Greek.

Compellingly, look at:

- the timeline

- the artificiality

- the Greek prestige influence

- Hebrew being codified in a Greek intellectual environment

Biblical Hebrew - the actual language of the biblical books - shows signs of being systematized after and under the influence of Greek.

Its appearance after the LXX, its narrative structures, and its lexicon support the hypothesis that it was engineered to create an ethnic counter-narrative in the priesthood wars of the Hellenistic period.

The Hebrew lexicon contains many Greek loanwords.

This is uncontroversial.Examples:

- κάμπος → כַּמָּל

- πάπυρος → פפרוס

- σάνδυξ → שַׁנְהוּט

- γενεά → גֵּנֶה / γενεαλογικά terms

Many appear in the Torah itself (Genesis, Exodus) according to LXX philologists.

Hebrew script is derived from Phoenician but Biblical Hebrew grammar is very late.

Meaning the alphabet is old, but the language system is late.

Biblical Hebrew grammar has signs of conscious engineering.

This includes:

- forced triliteral roots

- artificial binyan regularity

- waw-consecutive

- artificially archaized forms

- strange tense-aspect mismatches

These features make far more sense if:

The language was regularized by scribes long after Greek was already the prestige language.

Could Hebrew have been constructed using Greek as a blueprint?

If one throws off the conventional narrative and looks only at:

- chronology

- morphology

- semantics

- narrative style

Then the idea becomes plausible, especially if:

- a priestly group wanted an independent identity from the Greek-speaking world

- they wanted an older-looking script to retrofit a pre-existing Greek Scripture into a nationalist past

- they needed a “proto-language” to backdate their stories

This is a known phenomenon:

- Gothic Bible language invented by a bishop (Wulfila)

- Classical Arabic regularized in the 8th century for the Qur’an

- Sanskrit artificially frozen for Vedic authority

- Church Slavonic engineered as a liturgical language

Inventing a language to legitimize a religious narrative is historically normal.

So this framework becomes much less surprising:

- Hebrew appears when it “had to appear,” precisely after the LXX, to create a retroactive ethnic identity and priestly lineage.

There was No Hebrew Libraries or Literature before ~250BCE

For some reason, we see ZERO Hebrew literature or libraries in the historical record (apart from minor inscriptions or blessings).

After 290BCE, the date the Greek Septuagint was authored in Alexandria, we'll start to see some Hebrew emerge in the Dead Sea Scrolls dated later around 150BCE-100CE.

No Archaeological Evidence of a Hebrew Literary Library Before the Hellenistic Period

To date, no physical library, archive, or codex of Hebrew literature has ever been found from the Bronze or early Iron Ages (i.e. 1200-600 BCE).

What has been found are small ostraca (potsherds with ink writing) and inscriptions (e.g. Gezer Calendar, Siloam Inscription, Kuntillet ʿAjrud). These are brief administrative notes or blessings - not literature.

There are no manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible, prophets, psalms, or any continuous literary Hebrew work from those centuries.

All claims of earlier Hebrew “biblical” texts are theoretical and not supported by archaeological finds.

The Earliest Actual Hebrew Literary Manuscripts:

- The Dead Sea Scrolls (ca. 150 BCE – 70 CE)

The Dead Sea Scrolls, discovered beginning in 1947 in caves near Qumran, are the earliest known Hebrew manuscripts of any substantial length or literary content.

- Date: mid-2nd century BCE to 1st century CE

- Contents: copies of Torah, Prophets, Psalms, and other sectarian writings

- Languages: Hebrew (majority), Aramaic (significant minority), and Greek (few fragments)

That is the first archaeological evidence of Hebrew literature.

Before that: nothing - no scrolls, no codices, no libraries.

Conclusion

There has never been an archaeological discovery of a pre-Hellenistic Hebrew library or literary corpus.

The first known Hebrew literary manuscripts are the Dead Sea Scrolls (~150 BCE).

The earliest known Old Testament as an actual written literary work is the Greek Septuagint, not a Hebrew text.

The Documentary Hypothesis is Flawed - this is how Hebrew was ever dated to 10th BCE

The so-called “10th-century BCE Hebrew” is a paleographic convention, not a textual discovery. And was proposed rather late / recently in 19th–20th CE.

It refers to alphabetic inscriptions found in layers dated to the 10th BCE, not to Hebrew literature.

When scholars attach that early date to biblical writings, they rely on the Documentary Hypothesis — a literary reconstruction unsupported by any physical Hebrew manuscripts.

Thus, by empirical measure, the earliest Hebrew literature is from the Dead Sea Scrolls (2nd cent. BCE), and the earliest Old Testament as literature is the Greek Septuagint (3rd cent. BCE).

Documentary Hypothesis is a literary theory, not an archaeological method.

It posits that the Hebrew Bible was woven from older “documents” (J, E, D, P) supposedly composed between the 10th–6th centuries BCE.

However, there are no physical manuscripts of these hypothetical sources.

They were inferred based on stylistic differences within the existing Hebrew text — a text preserved only in late medieval copies (after 900CE) and in Greek centuries earlier (290BCE).

Thus, any “10th-century Hebrew literature” dated through the Documentary Hypothesis is purely theoretical.

What Is Actually Dated Empirically

Only three classes of Hebrew-related material can be dated physically:

- Short inscriptions (ostraca, seals, graffiti) - 10th–6th BCE by paleography.

- Not literature.

- Greek Septuagint papyri - 3rd cent BCE.

- Full literary corpus.

- Dead Sea Scrolls - 2nd BCE–1st CE.

- First Hebrew literary manuscripts.

Everything earlier is reconstruction, not evidence.

No Hebrew manuscripts predating the Septuagint exist.

- The earliest physical Hebrew literary manuscripts are the Dead Sea Scrolls (ca. 250 BCE – 70 CE).

- There is no manuscript evidence for a standardized Hebrew text before the Septuagint’s creation.

The Septuagint (LXX) predates the Masoretic Text (MT) by centuries.

- The Septuagint translation began in 3rd–2nd centuries BCE in Alexandria.

- Physical fragments such as Papyrus Rylands 458 (≈ 150 BCE) confirm its existence by then.

- This makes the LXX the earliest extant Old Testament literature.

The Masoretic Text was standardized a millennium later.

- The Masoretes fixed the Hebrew text between the 7th–10th centuries CE.

- The Aleppo Codex (≈ 920 CE) and Leningrad Codex (≈ 1008 CE) are the earliest complete MT manuscripts.

- Before this, Hebrew manuscripts show textual diversity, not a single uniform text.

Dead Sea Scrolls show multiple textual traditions.

- Some scrolls align more with the Septuagint than with the later Masoretic Text (e.g. 4QJerᵃ follows the LXX’s shorter Jeremiah).

- This demonstrates that the MT did not yet exist as a fixed text when the LXX was made.

Stylistic Analysis from Complexity - Hebrew is coarse concrete vs Greek nuanced advanced technical abstract

- Paleo Hebrew is coarse concrete

- 3rd Grade Level - analogy: compared to English at the 3rd grade level.

- Language is More coarse, supporting concrete thought, but struggles with abstract or technical thoughts.

- Example: Cow Head plus Big Hole (refers to Nose). (reference from "Prophet Wars: Mystery Translation")

- Metaphysics are often represented as non-sensical, metaphorical, supernatural.

- Ancient Greek is technically nuanced abstract

- College Level - analogy: compared to English at the college level.

- Language is More technically nuanced, excels supporting both concrete and abstract thought.

- Example: Nose.

- Metaphysics are represented in precise technical language based in reality, or coded mystery language.

Many passages in the Hebrew old testament read at a “3rd grade” level (where metaphysics are represented as non-sensical, metaphorical, supernatural), while the Greek versions convey advanced, technical, and precisely nuanced descriptions of cognitive metaphysics and pharmakon mechanisms rooted in reality. The Greek writing is practical, in that a pharmakon practitioner in the mystery schools could experience the effects themselves, while the Hebrew simplification go outside reality to explain their concepts. This suggests that the more detailed, philosophically rich Greek texts, rooted in reality of pharmakon magia, likely predate the Hebrew versions.

The Hebrew writings often appear to be crude adaptations or simplifications of the Greek, constrained by the language’s limited expressive capacity. Speakers of early Paleo Hebrew, particularly before 400 BCE when that language died out, would have struggled to grasp complex metaphysical or technical concepts, reducing them to oversimplified narratives.

In effect, the Paleo-Hebrews seem to have inherited ideas from the more sophisticated Hellenic tradition, but filtered through a lens that obscured nuance and depth, producing what can appear as naïve or garbled renditions of originally advanced thought.

Examples:

Comparing Enoch Greek vs Hebrew

In Enoch:

- In the Hebrew: we have the Nephilim alien visitors...

- In the Ancient Greek Language: we have mystery and pharmakon and putting children into ripe virgins

Which one is nonsensical?

Which one is supernatural?

Which one is improbable in the reality you live every day?

Which one could happen?

Which one makes sense?

Which one seems like the translators didn't understand?

Genesis 2:18

Where the Hebrew text uses the word ezer (עֵזֶר) for Eve, which is traditionally translated as “helper”:

- Hebrew:

“I will make a helper suitable for him” — ezer kenegdo (עֵזֶר כְּנֶגְדּוֹ)

Here, the Hebrew ezer carries the sense of “assistant” or “one who comes to help,” often used in the Hebrew Bible for God as a helper to Israel, but it’s vague and contextually ambiguous—it reads as subordinate or supporting.

- Greek Septuagint:

18 Καὶ εἶπεν Κύριος ὁ θεός Οὐ καλὸν εἶναι τὸν ἄνθρωπον μόνον· ποιήσωμεν αὐτῷ βοηθὸν κατ᾽ αὐτόν.

“I will make him a βοηθόν (boēthón) corresponding to him” — poiesō autōn boēthon pros auton (ποιήσω αὐτὸν βοηθὸν πρὸς αὐτόν)

The LXX boēthón is richer: in classical Greek, it can imply a comrade in arms, a peer who fights alongside you, not merely a subordinate assistant. This choice gives the text a military or regimented undertone:

- Eve is not just "a helper", she is a strategic partner or collaborator, at his level of leadership, capable of acting in conjunction with Adam in a coordinated effort.

Significance

This is a clear example where the Hebrew reads as simple, almost naïve (“helper”), whereas the Greek conveys a technical, sophisticated concept of partnership and agency, consistent with Hellenic ideas of hierarchical but collaborative structures (like a phalanx or military unit). It supports the point that the Greek preserves the advanced original idea, while the Hebrew simplifies it.

Genesis 1:1–2

Hebrew (MT style simplified):

"In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was formless and void..."

- The Hebrew is very basic, almost literal “3rd grade” descriptive level. It gives the outline of creation, but little technical or conceptual detail.

- The story reads like a simplistic narrative or fairy tale: earth is formless → God fixes it. Very straightforward, almost storybook.

Greek Septuagint:

2 ἡ δὲ γῆ ἦν ἀόρατος καὶ ἀκατασκεύαστος, καὶ σκότος ἐπάνω τῆς ἀβύσσου· καὶ πνεῦμα θεοῦ ἐπεφέρετο ἐπάνω τοῦ ὕδατος.

"In the beginning God made the heaven and the earth. And the earth was invisible and unfinished, and darkness was upon the abyss..."

- The Greek uses technical, abstract philosophical vocabulary: ἀόρατος (invisible), ἀτελής (unfinished), χάος (chaos/abyss).