Threshing Floors - in Ancient Ritual and Theater

Threshing floors in antiquity were far more than simple agricultural spaces; they carried profound social, religious, and symbolic significance, often intersecting with ritual and initiation practices.

- Evolution of the threshing floor

- Threshing Floors as Ritual & Sacred Space

- Ergot, Hoof Marks, and The Horse's Circle

- Threshing Floor - Gymnasium - Theater

- Theater as Ritualized Initiation

- Initiatory Mechanics

- Shapes, Geometry, and the Sacred

- Summary

Evolution of the threshing floor

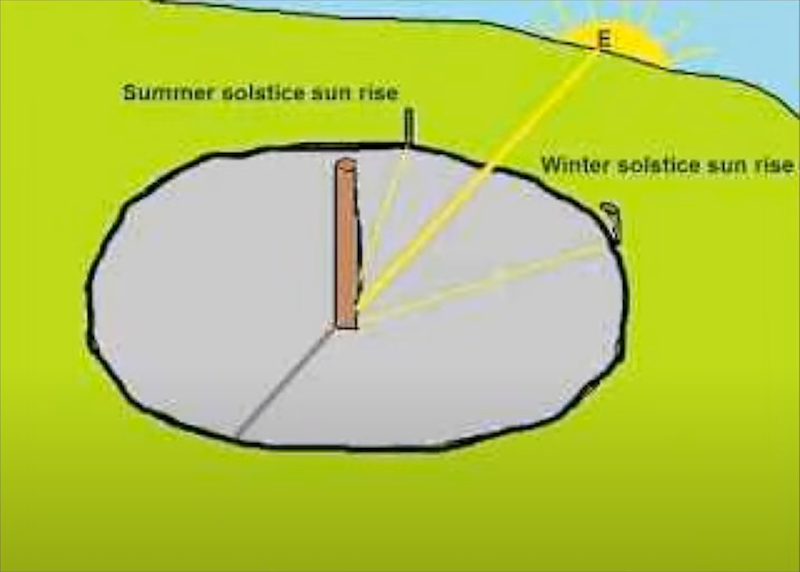

Sundial evolved into threshing floors — spaces where time, harvest cycles, and ritual life intersected

Sundial threshing Floor

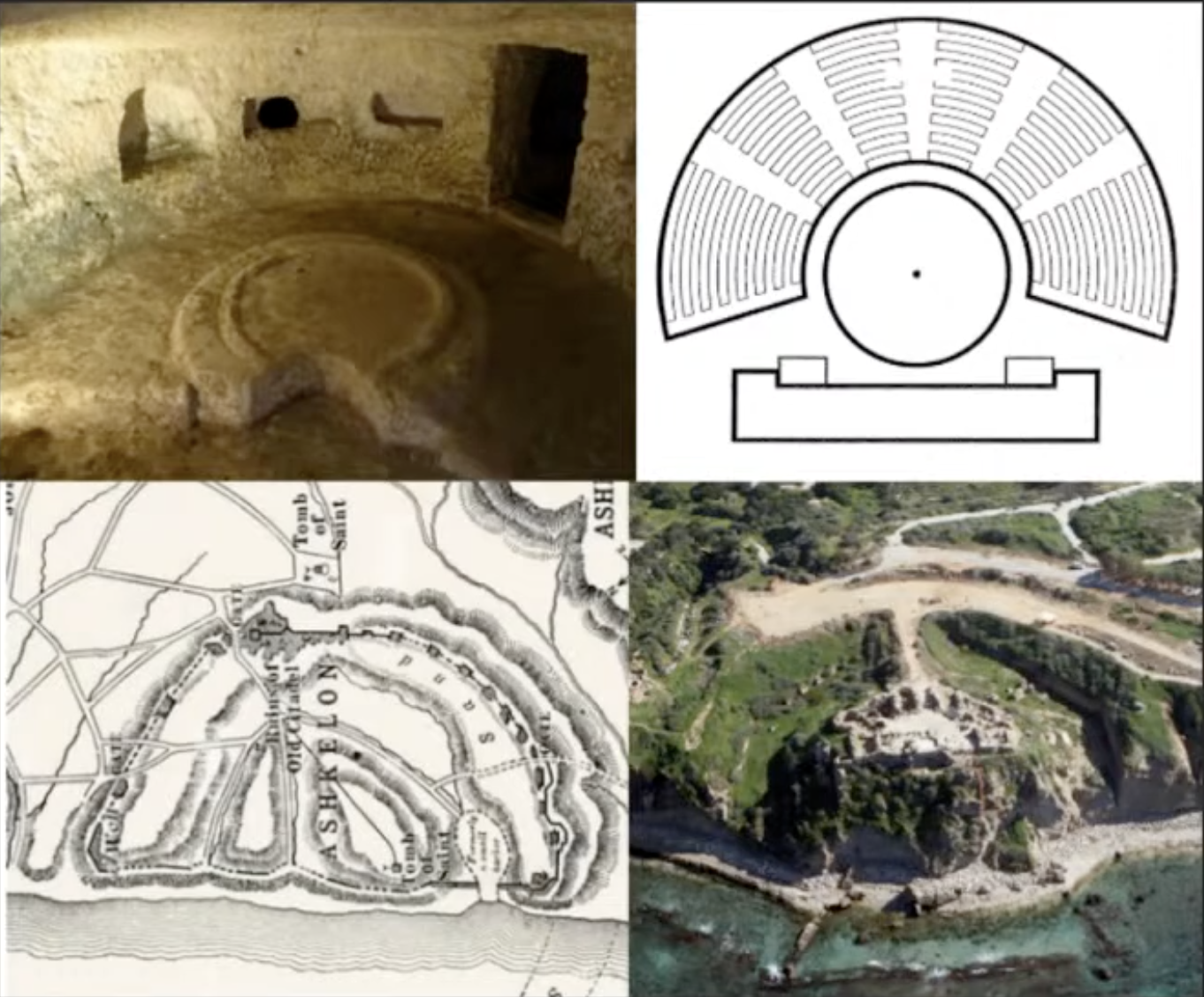

Amphitheater - Omega Shaped (Horseshoe) from the hellenized period.

Threshing floor is already a centralized spot for rituals.

Used as amphitheater the rest of the year.

Dionysus festivals

Rituals dont go away, becomes theater, best poet wins a goat.

3 kinds of plays, tragedy (life, love, death, loss), comedy, satry play,

Tragedy grows out of dithyramb.

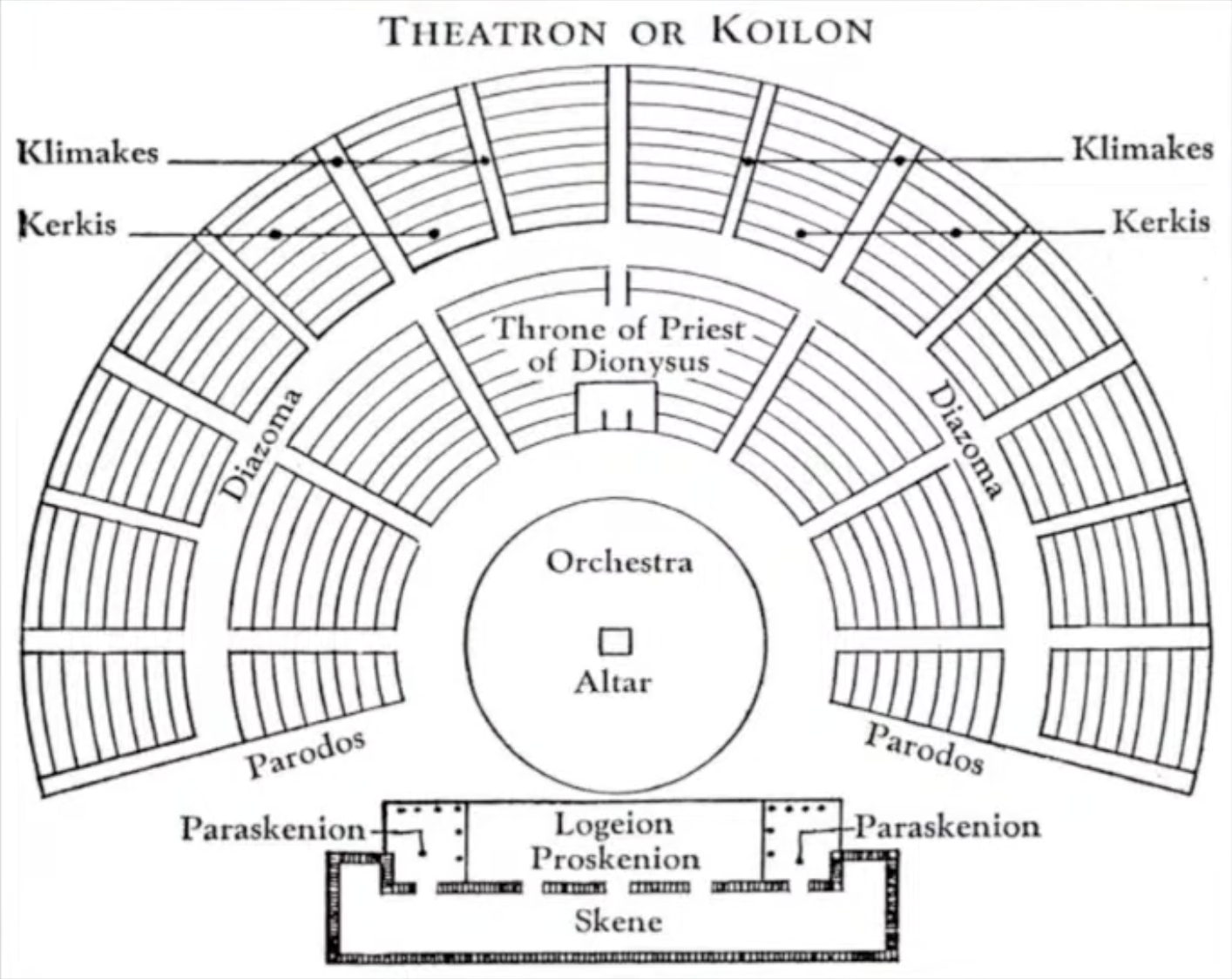

Skene is where they change, show different scenes.

Also, this omega shape is a schematic for vagina/skenes glands.

Threshing Floors as Ritual & Sacred Space

- Sundials evolved into threshing floors — spaces where time, harvest cycles, and ritual life intersected.

- Because it was central to the community’s sustenance, the threshing floor was a place of collective labor, making it socially significant and public.

- A threshing floor was circular, elevated, and public, already resembling a ritual stage.

- The process of separating grain from chaff involved

- beating harvested grain with flails, or

- Animals walked in circles on the floor to separate grain from chaff, and the hoof-marks (linked with ergot fungus, claviceps purpurea) gave the space a further psychoactive/entheogenic association, since ergot was central to both poisoning and mystery-drug traditions.

Ergot, Hoof Marks, and The Horse's Circle

On the threshing floor, where oxen and horses circled to crush the sheaves, their hoof-marks in the clay became more than just traces of labor. The ancients noticed that diseased barley often produced black, spur-like growths—what we now call ergot. These looked like hoof-nails or claws, and Latin writers even called them clavi (nails, hoof-spurs). In medical and agronomic texts, this “hoof-spur” disease was linked to madness, stumbling, and gangrene in both animals and humans.

Both Greek and Latin writers described them: the Greeks as ἔρυσίβη (“rust, blight”), the Romans as spinae frumentorum (“grain-thorns”), while Latin medical writers also used clavus (“nail, hoof-nail”).

So the hoof became a double symbol: the literal trace of the animals who turned the floor, and the figurative shape of the poison that rode the grain. In mystery-cult imagination, this connection was fertile — hoof-marks in the sacred circle were already signs of Dionysian frenzy, while the hoof-shaped fungus provided the intoxicant that drove initiates into ecstasy. The hoof thus marked both the floor of ritual and the hidden pharmakon within the harvest.

Farmers observed that animals who ate such infested grain often stumbled or became lame, their hooves rotting — a vivid symptom of ergotism. Thus in ancient agricultural and medical literature ergot was literally tied to “hoof-marks,” both in its appearance and its effects.

Later, in mystery-cult language where hoofs and the horse’s circle already carried ecstatic and Dionysian resonance, this resemblance gave ergot a further symbolic charge as an intoxicant growing out of the very grain that was threshed under animal hooves.

Albert Hoffman and Jon Ott noted later in Road to Eleusis, that Ergot could be safely extracted using Cold Water as long as the toxic solids were filtered out. Leaving behind the non-polar (oil/alcohol) soluble ergo-toxins (e.g. water and oil dont mix). It's been supposed that a water-extraction of Ergot was used in ancient rites like Eleusinian Mysteries and alluded to in the Old Testament as well.

- Latin clavus (“nail, hoof-nail”)

Modern name for Ergot:

- Claviceps Purpurea (purple slerotia on wheat/rye/barley)

- Claviceps Paspali (rust like substance on Distichum grass)

Ancient names for Ergot:

- On grain (esp. barley, rye, wheat): Greek writers sometimes used words like ἔρση / ἔρσηρον (dew-like, moldy growth), ἄκανθα σιτίων (thorn of grain), or simply ἰὸς σίτου (“poison of the corn”). Latin agronomists (Pliny, Columella) mention a nigrities or spuriae fruges — dark, spurious kernels among the true seed.

- On grasses (paspalum): the purple or rust-like growths were described as nigrae spicae (black ears) or segetum vitia (blights of crops). These weren’t sharply distinguished from rusts or smuts — the ancients lumped fungal diseases together as “blights” (robigo, ura, rubigo).

- ἔρυσίβη (ergsíbē) — in Theophrastus (Historia Plantarum 8.7.2), used broadly for “blight” or “rust” on grain, but commentators note that in some passages it seems to describe the black, spur-like excrescences that match ergot.

- σπέρμα πυρῶν ἐξέπεσεν ὡς κέρας / “horn-like growths on wheat” — pseudo-Aristotelian De plantis refers to horn-shaped outgrowths, again suggestive of ergot.

- In Latin agronomists like Pliny (Naturalis Historia 18.17, 26) and Columella (2.2.23), the term clavus (“nail” or “hoof-nail”) was used for diseased grains. This matches the appearance of ergot sclerotia — hard, black, curved “hoof-like nails” protruding from the ear.

Most common ancient terms were ἔρυσίβη in Greek and clavus in Latin.

Threshing Floor - Gymnasium - Theater

- Threshing floors also doubled as wrestling pits, sacred groves, and sacrifice spaces, connecting them to the gymnasium (where training, contests, and initiation happened).

- When not in use for agriculture, the threshing floor became a stage for ritual storytelling — myths, hymns, and later, theatrical performances.

- The orchestra (literally, “dancing space”) of the Greek theater directly preserves the circular threshing-floor shape. The priest’s central chair or altar echoes the central ritual officiant in threshing-floor ceremonies.

Theater as Ritualized Initiation

- From Dionysian rites, theater evolved as a civic initiation rite for whole communities:

- Tragedy (τραγῳδία = “goat-song”): linked with goat sacrifice and satyr choruses; dramatized taboo or horrific themes (incest, parricide, etc.), mirroring the initiatory “death-and-rebirth” ordeal.

- Comedy: followed tragedy to restore balance, offering catharsis through laughter.

- The festival of Dionysia in Athens was a city-wide initiation—a ritualized reenactment of Dionysian frenzy but now domesticated into drama, competition, and civic unity.

- Masks and the skēnē (scene-house) evolved directly from ritual practice: actors changed personas just as initiates took on new identities in mystery rites.

Initiatory Mechanics

- Tragedy and comedy mirror the initiation pattern:

- Tragedy = symbolic death, confrontation with horror, catharsis.

- Comedy = renewal, release, rebirth into communal joy.

- Both mirror the same experience as mystery cult rites: ritual intoxication, ecstatic loss of self, confrontation with death, then return to life with renewed identity.

- The entheogenic context: wine, goat milk, cakes, fumigation (cannabis, poppy, opium, incense) all echo the mystery-cult pharmaka and explain the ecstatic frenzy.

Shapes, Geometry, and the Sacred

- Sacred spaces (triangle, circle, horseshoe, semicircle) were language in themselves, shaping how ritual and theater embodied divine order.

- The threshing floor circle was divided by the skēnē, symbolically cutting the round into a semicircle - foreshadowing the Roman amphitheater form.

Summary

- Threshing floors began as agricultural necessity but became ritualized spaces.

- These spaces naturally evolved into theaters, where initiation themes were preserved as communal drama.

- Theaters were essentially urbanized threshing floors — temples of Dionysus, where the whole polis underwent ritual death and rebirth through tragedy and comedy.